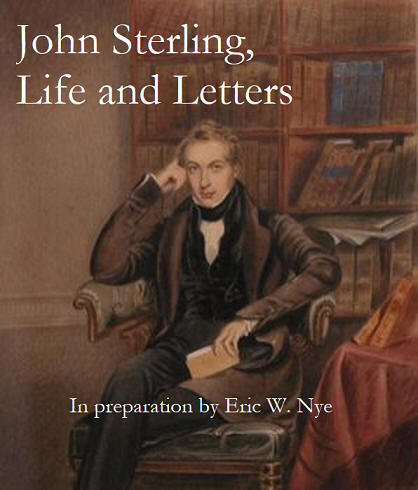

Man of letters, poet, and

religious thinker, John Sterling had a special gift for literary friendships,

and he expressed that gift powerfully toward the Carlyles. In the

conclusion of his Life of John Sterling (1851), Thomas writes, "Here,

visible to myself, for some while, was a brilliant human presence,

distinguishable, honourable and lovable amid the dim common populations; among

the million little beautiful, once more a beautiful human soul: whom I, among

others, recognised and lovingly walked with, while the years and the hours

were." Sterling's death from consumption left a general sense of promise

unfulfilled, yet if his life can be detached from the pervasive Victorian sense

of valediction, it reveals a complex and more rewarding intellectual pilgrimage.

John Sterling was born in 1806 at Kames Castle, on the Isle of Bute,

where his father, Edward, a retired captain of militia, had taken up

farming. In 1809 the family moved to the south of Wales while the father

cultivated various connections, finally establishing a lifelong association with

the Times in London, first as a leader-writer, and eventually as

co-proprietor. Edward Sterling (1773-1847) and his wife Hester Coningham

Sterling (1783-1843) were closely linked with the Carlyles in their own right,

as was John's elder brother, Col. Anthony Sterling (1805-1871). All lived

in Knightsbridge in London after 1820. John's poor health prevented him

attending public school, but he studied at Greenwich School and Christ's

Hospital before attending Glasgow University, 1822-24, and finally Trinity

College, Cambridge in 1824.

At Cambridge Sterling quickly distinguished himself in debates at the Union

Society, becoming its president in 1827, and among the fledgling Cambridge

Apostles. Torn between careers in law, politics, the church, and

literature, Sterling migrated to Trinity Hall in 1826 and then back to London.

With F. D. Maurice he founded the Metropolitan Quarterly Magazine,

styled after the great journals of the day, and within a few years assumed

ownership and control of the new periodical the Athenaeum.

At the London Debating Society he met John Stuart Mill who recalls how Sterling

and Maurice represented "a second Liberal and even Radical party, on totally

different grounds from Benthamism and vehemently opposed to it; bringing into

these discussions the general doctrines and modes of thought of the European

reaction against the philosophy of the eighteenth century" (Autobiography,

128). The main intellectual influence on Sterling at this time was Samuel

Taylor Coleridge whom he met at Highgate and whose theological writings Sterling

later inherited as joint executor along with his tutor from Trinity, Julius

Charles Hare.

Sterling became devoted to Coleridge, serving as

disciple and amanuensis at a time when both were interested alike in German

fiction and the higher criticism. J. C. Hare promoted the friendship and

owned himself perhaps the finest library of German authors in England.

This constellation of talent could only have been envied by Carlyle who was then

at work on his own translation of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister (1824),

Life of Friedrich Schiller (1825), and German Romance (1827).

And like Carlyle in Sartor Resartus, Sterling wrote an autobiographical

novel of crisis called Arthur Coningsby (1833) set in the French

Revolution. Like his leading character Sterling suffered serious loss of

political idealism in the debacle ensuing from his support of an abortive

campaign to free Spain from tyrannical rule. The Spanish affair involved

many of Sterling's Cambridge friends, Richard Chenevix Trench, J. W. Blakesley,

Charles Buller, Arthur Henry Hallam, Alfred Tennyson, John Mitchell Kemble, and

Charles Barton. Late in 1830 Sterling married Susannah Barton whose

family included the influential Bordeaux wine merchants. He planned to

return to Cambridge, take his degree, and then study in Germany, but that winter

his health suffered its first serious setback. When he recovered, he

accepted a proposal to seek a better climate in the West Indies

where his uncle

owned a plantation.

where his uncle

owned a plantation.

Within

weeks of their arrival in St. Vincent, the plantation was battered by a

hurricane, and two months later their first child was born. Sterling

corresponded with his father's newspaper about the condition of slaves and

slave-owners and experimented with various forms of education. Returning

to London a year later, he hoped to recruit a schoolmaster for the plantation

but was persuaded by Coleridge to renew his German studies in Bonn with A. W.

Schlegel. There he met J. C. Hare who had left his fellowship in Cambridge

and was traveling the continent before assuming the family living at

Herstmonceux in Sussex. Hare offered Sterling his curacy, and Sterling

accepted, despite his uncertain health. He was ordained Deacon in 1834 and

seems always to have considered the clergy to be what Coleridge called "a

clerisy," a distinction Carlyle may not have accepted. For over a year

Sterling served a parish of 1400 people until doctors in London warned him

against the dangers of continuing. On one of these visits to London in

1835 he first met Thomas Carlyle in Mill's office. Hoping for an

appointment to the English chaplaincy in Rome or as an inspector of schools in

the West Indies, Sterling was forced by his health to move with his family to

Bordeaux where for some time he became one of the most celebrated contributors

of poetry and prose to Blackwood's Magazine. This attachment

continued even after a cholera outbreak drove him to return to London, leave his

family with his parents, and spend the winter in Madeira.

condition of slaves and

slave-owners and experimented with various forms of education. Returning

to London a year later, he hoped to recruit a schoolmaster for the plantation

but was persuaded by Coleridge to renew his German studies in Bonn with A. W.

Schlegel. There he met J. C. Hare who had left his fellowship in Cambridge

and was traveling the continent before assuming the family living at

Herstmonceux in Sussex. Hare offered Sterling his curacy, and Sterling

accepted, despite his uncertain health. He was ordained Deacon in 1834 and

seems always to have considered the clergy to be what Coleridge called "a

clerisy," a distinction Carlyle may not have accepted. For over a year

Sterling served a parish of 1400 people until doctors in London warned him

against the dangers of continuing. On one of these visits to London in

1835 he first met Thomas Carlyle in Mill's office. Hoping for an

appointment to the English chaplaincy in Rome or as an inspector of schools in

the West Indies, Sterling was forced by his health to move with his family to

Bordeaux where for some time he became one of the most celebrated contributors

of poetry and prose to Blackwood's Magazine. This attachment

continued even after a cholera outbreak drove him to return to London, leave his

family with his parents, and spend the winter in Madeira.

Sterling's friendship and correspondence with the Carlyles were

well-established by this time, and Thomas figures conspicuously in Sterling's

novella, The Onyx Ring, published serially in Blackwood's late

in 1838 and reissued posthumously in Boston as a book. Here Sterling

attempts to reconcile the conflicting claims of Carlyle, Goethe, Hare,

Coleridge, and others over his evolving career. By wearing the onyx ring

this tale's protagonist is permitted to spend a week inside the being of another

soul and thereby to reflect on human existence from a variety of perspectives.

In the persona of a poet the protagonist encounters the Carlyle-figure and is

reproached for idleness and the absence of earnest striving. Yet

Sterling's commitment to poetry survived Carlyle's criticism. His poems

were collected by Moxon in 1839, praised by Henry Nelson Coleridge in the

Quarterly Review, and pirated in America three years later despite

Emerson's attempt to prepare an authorized edition. His verse satire,

The Election, was published by Murray and reviewed by Mill who called it

the best of its kind since Byron. Like Coleridge, Sterling wanted to

combine religion and art, faith and the imagination, historical Christianity and

the modern experiment. And he tried unsuccessfully to persuade Carlyle to

pursue such a synthesis.

In the mid-1830s Mill assumed editorship of the

London and Westminster Review and welcomed Sterling's articles and

poetry. They toured together in Rome in 1838 before Sterling's return to

England and residence in Clifton where his friends included the Stracheys, Dr.

John Addington Symonds, and Francis W. Newman. In October 1839 Mill

published Sterling's splendid controversial review article on Carlyle.

Thomas almost blushed: "My friend, what a notion you have got of me!" he wrote

Sterling. "I will say there has no man in these Islands been so reviewed

in my time; it is the most magnanimous eulogy I ever knew one man utter of

another man whom he knew face to face" (Letters 11:192). Later

Carlyle called it "the first generous human recognition, expressed with heroic

emphasis, and clear conviction visible amid its fiery exaggeration, that one's

poor battle in this world is not quite a mad and futile, that it is perhaps a

worthy and manful one, which will come to something yet: this fact is a

memorable one in every history; and for me Sterling, often enough the stiff

gainsayer in our private communings, was the doer of this" (Life of Sterling,

248-49). In spite of his praises, Carlyle may not have grasped the complex

purposes of this essay, either public or private. Privately Sterling hoped

to win Carlyle to a juster understanding and acceptance of Coleridge, an

understanding Mill was himself pursuing in the composition of his own essay on

Coleridge at just this time. Publicly Sterling hoped through the

London and Westminster Review to win a new audience for his friend Carlyle,

who refused to be called a radical just as he shuddered to be thought a

Coleridgean, though he was in fact a little of each. An essay by a former

clergyman in a radical journal defending the increasingly famous critic of the

follies of Christendom was bound to undermine Sterling's standing in the church.

Additional doubts arose in some circles with the formation of the Sterling Club,

an association of literary men that met for dinner monthly in London to

celebrate the spirit of friendship embodied by John Sterling. The Club

survived Sterling's death and ignited suspicions of freethinking and impiety

among religious critics at about the time Carlyle published his Life of John

Sterling (1851).

In

the aftermath of his Carlyle article, Sterling published several installments of

his translation of Goethe's Dichtung und Wahrheit in Blackwood's

and contributed to Maurice's Educational Magazine, the latter

suggesting that his estrangement from friends in the church was by no means

absolute. He dedicated his collection of poems late in 1839 to his friend

and mentor J. C. Hare, soon to become Archdeacon, and began composing a verse

drama based on the life and death of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford two

hundred years earlier. At this time, too, Sterling began corresponding

with Ralph Waldo Emerson to whom he later dedicated Strafford (1843).

The two enjoyed an instant affinity, both having left the clergy and embarked on

a life of letters.

In

the aftermath of his Carlyle article, Sterling published several installments of

his translation of Goethe's Dichtung und Wahrheit in Blackwood's

and contributed to Maurice's Educational Magazine, the latter

suggesting that his estrangement from friends in the church was by no means

absolute. He dedicated his collection of poems late in 1839 to his friend

and mentor J. C. Hare, soon to become Archdeacon, and began composing a verse

drama based on the life and death of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford two

hundred years earlier. At this time, too, Sterling began corresponding

with Ralph Waldo Emerson to whom he later dedicated Strafford (1843).

The two enjoyed an instant affinity, both having left the clergy and embarked on

a life of letters.

A hemorrhage in his lungs drove Sterling from Clifton

to Falmouth early in 1840 to await a ship to Madeira. The climate there,

both intellectual and meteorological, proved suitable for an extended stay, and

he was quickly befriended by the influential Quaker family of Barclay and

Caroline Fox. John Stuart Mill attended his dying brother there, and

Derwent Coleridge ran a school nearby. Increasingly Sterling turned away

from theological controversy toward poetry. In the spring of 1841 he

bought a house in Falmouth and moved his family there. He lectured to

acclaim at the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, founded a decade earlier by

the Fox family. At the beginning of 1842 his friend from Madeira J.

M. Calvert died in Falmouth, and at about the same time came news that

Sterling's investments in an American canal company had been lost. Hoping

to supplement his friend's literary income, Carlyle solicited essays from

Sterling for Forster's Foreign Quarterly Review. When Sterling

returned from a journey to Malta and Italy midyear, he composed an essay on

Tennyson's Poems (1842) for Lockhart's Quarterly Review, one

of the most influential early appreciations of that poet.

In

early 1843 Sterling suffered a relapse while his mother, too, fell gravely ill.

On Good Friday his daughter was born in Falmouth, but Sterling's wife suffered

complications from the delivery. News arrived of his mother's death on

Easter Sunday in London, and a short time later his wife also perished.

Sterling was devastated. In the months that followed with the help of the

Maurices he arranged schooling for his children in London and to be closer moved

from Falmouth to the Isle of Wight where he supervised rebuilding of a house at

Hillside near Ventnor. He continued writing his ottava rima tale on

Coeur-de-Lion, to which Carlyle responded, "if a man would write in metre, this

sure enough, was the way to try doing it" (Life 321). In January

1844 Sterling appears to have proposed marriage to Caroline Fox in Falmouth, and

the bright, lively young woman declined, influenced by her parents' concerns about Sterling's health and his situation outside the

Quaker fellowship. This, too, deadened Sterling's spirits in his long last

winter at Hillside. His bleeding worsened in April and through the summer

he wrote a series of powerful letters to his first-born son in London.

Carlyle describes their last visit together in London and gives examples of

Sterling's letters from these final months. Attended by Mrs. Maurice and

his own brother, Anthony, Sterling died in the night of 18 September 1844.

Carlyle's tribute seven years later at the end of his Life of John Sterling

(1851) is still extraordinarily moving. He was not alone in contemplating

such a tribute of friendship. Mill and Emerson both projected biographies,

and Hare prefixed a long, defensive Memoir to the first volume of his

collection of Sterling's Essays and Tales (2v, 1848). The

so-called religious press had its own objections to Sterling's liberal

tendencies, objections catalyzed by the scandalous suggestion that dinners of

the Sterling Cub omitted the speaking of grace.

her parents' concerns about Sterling's health and his situation outside the

Quaker fellowship. This, too, deadened Sterling's spirits in his long last

winter at Hillside. His bleeding worsened in April and through the summer

he wrote a series of powerful letters to his first-born son in London.

Carlyle describes their last visit together in London and gives examples of

Sterling's letters from these final months. Attended by Mrs. Maurice and

his own brother, Anthony, Sterling died in the night of 18 September 1844.

Carlyle's tribute seven years later at the end of his Life of John Sterling

(1851) is still extraordinarily moving. He was not alone in contemplating

such a tribute of friendship. Mill and Emerson both projected biographies,

and Hare prefixed a long, defensive Memoir to the first volume of his

collection of Sterling's Essays and Tales (2v, 1848). The

so-called religious press had its own objections to Sterling's liberal

tendencies, objections catalyzed by the scandalous suggestion that dinners of

the Sterling Cub omitted the speaking of grace.

Sterling suffered

the curious fate of getting so much exposure in his biographies that readers

have subsequently assumed his story was told--told even to excess. Yet

these were polemical biographies. Carlyle's portrait of the brave liberal

defying the bounds of orthodox Christian speculation and perishing in his quest

for something better, or Hare's of the Faustian soul saved in the end by his

acceptance of grace, neither can fully satisfy a modern reader.

After Henry James, Sr., met the London literati in the 1840s, he remarked:

"Mr Mill was the best of the lot excepting Sterling, who was the truest man I

ever met. Sterling was a perfectly delightful man, just the antipodes of

Carlyle and the only man Carlyle had any sincere attachment to. Sterling

was the only man in England who seemed like an American in spirit and manners.

He talked freely, was jocund, and was dying in perfect confidence."

And

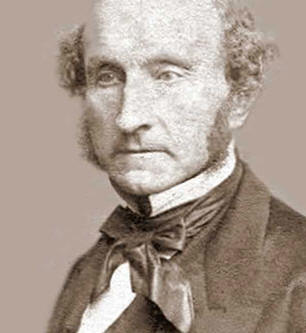

in his Autobiography (1873) John Stuart Mill records this appraisal of

Sterling.

"With

Sterling I soon became very intimate, and was more attached to him than I have

ever been to any other man. He was indeed one of the most loveable of men.

His frank, cordial, affectionate and expansive character; a love of truth alike

conspicuous in the highest things and the humblest; a generous and ardent nature

which threw itself with impetuosity into the opinions it adopted, but was as

eager to do justice to the doctrines and the men it was opposed to, as to make

war on what it thought their errors; and an equal devotion to the two cardinal

points of Liberty and Duty, formed a combination of qualities as attractive to

me, as to all others who knew him as well as I did. With his open mind and

heart, he found no difficulty in joining hands with me across the gulf which as

yet divided our opinions."

"With

Sterling I soon became very intimate, and was more attached to him than I have

ever been to any other man. He was indeed one of the most loveable of men.

His frank, cordial, affectionate and expansive character; a love of truth alike

conspicuous in the highest things and the humblest; a generous and ardent nature

which threw itself with impetuosity into the opinions it adopted, but was as

eager to do justice to the doctrines and the men it was opposed to, as to make

war on what it thought their errors; and an equal devotion to the two cardinal

points of Liberty and Duty, formed a combination of qualities as attractive to

me, as to all others who knew him as well as I did. With his open mind and

heart, he found no difficulty in joining hands with me across the gulf which as

yet divided our opinions."

Sterling links the age of Coleridge with that

of Carlyle and Mill. By his commitment to poetry and theology he embodies

the idea of a Coleridgean clerisy in times of increasing contentiousness.

That he could crystalize friendships across such a spectrum of opinion remains a

vivid testimony to the powers of his mind, imagination, and character.

Selective Bibliography in chronological order:

J. C. Hare, "Sketch

of the author's life," Essays and Tales by John Sterling, 2 vols.

(1848).

T. Carlyle, The Life of John Sterling (1851).

W.

Coningham, ed., Twelve Letters Originally Printed for Private Circulation

(1851).

J. S. Mill, Autobiography (1873).

H. Pym, ed.,

Memories of Old Friends: Being Extracts from the Journals and Letters of

Caroline Fox, 3rd edn, 2 vols. (1882).

F. Maurice, ed., The Life of

Frederick Denison Maurice Chiefly Told in His Own Letters, 3rd edn, 2 vols.

(1884).

M. Trench, ed., Richard Chenevix Trench, Archbishop: Letters and

Memorials (1888).

J. R. Dasent, ed., Letters from John Sterling to

George Webbe Dasent, 1838-1844 (1914).

R. W. Emerson, The Letters of

Ralph Waldo Emerson, ed. R. L. Rusk (1939).

A. K. Tuell, John

Sterling: Representative Victorian (1941).

J. S. Mill, The Earlier

Letters of John Stuart Mill: 1812-1848, ed. F. E. Mineka (1963).

T. and

J. W. Carlyle, The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle,

Duke-Edinburgh edn, ed C. R. Sanders, C. Ryals, K. J. Fielding, et al. (1970- ).

P. Allen, The Cambridge Apostles: the Early Years (1978).

R. L.

Brett, ed., Barclay Fox's Journal (1979).

N. M. Distad, Guessing

at Truth: the Life of Julius Charles Hare (1979).

E. W. Nye, "Carlyle

and John Sterling." Papers of the Carlyle Society (Edinburgh),

n.s. 1 (1988): 1-17.

E. W. Nye, "British Romantic Novelists, 1789-1832: John

Sterling." Dictionary of Literary Biography, ed. Bradford K.

Mudge (1992) 116: 343-50.

W. C. Lubenow, The Cambridge Apostles,

1820-1914 (1998).

E. W. Nye, "John Sterling." Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography, ed.C. Matthew, B. Harrison, et al. (2004- ).

E. W.

Nye, "John Sterling." Carlyle Enclyclopedia, ed. Mark Cumming (2004).

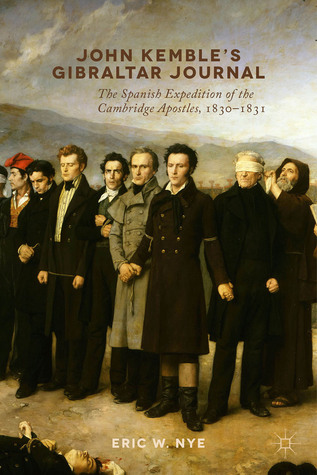

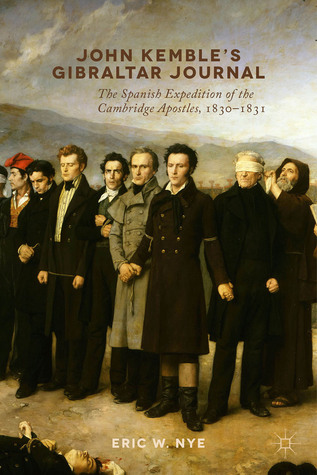

E. W. Nye, John Kemble�s Gibraltar Journal: The Spanish Expedition of the

Cambridge Apostles 1830�1831 (2015).

where his uncle

owned a plantation.

where his uncle

owned a plantation. condition of slaves and

slave-owners and experimented with various forms of education. Returning

to London a year later, he hoped to recruit a schoolmaster for the plantation

but was persuaded by Coleridge to renew his German studies in Bonn with A. W.

Schlegel. There he met J. C. Hare who had left his fellowship in Cambridge

and was traveling the continent before assuming the family living at

Herstmonceux in Sussex. Hare offered Sterling his curacy, and Sterling

accepted, despite his uncertain health. He was ordained Deacon in 1834 and

seems always to have considered the clergy to be what Coleridge called "a

clerisy," a distinction Carlyle may not have accepted. For over a year

Sterling served a parish of 1400 people until doctors in London warned him

against the dangers of continuing. On one of these visits to London in

1835 he first met Thomas Carlyle in Mill's office. Hoping for an

appointment to the English chaplaincy in Rome or as an inspector of schools in

the West Indies, Sterling was forced by his health to move with his family to

Bordeaux where for some time he became one of the most celebrated contributors

of poetry and prose to Blackwood's Magazine. This attachment

continued even after a cholera outbreak drove him to return to London, leave his

family with his parents, and spend the winter in Madeira.

condition of slaves and

slave-owners and experimented with various forms of education. Returning

to London a year later, he hoped to recruit a schoolmaster for the plantation

but was persuaded by Coleridge to renew his German studies in Bonn with A. W.

Schlegel. There he met J. C. Hare who had left his fellowship in Cambridge

and was traveling the continent before assuming the family living at

Herstmonceux in Sussex. Hare offered Sterling his curacy, and Sterling

accepted, despite his uncertain health. He was ordained Deacon in 1834 and

seems always to have considered the clergy to be what Coleridge called "a

clerisy," a distinction Carlyle may not have accepted. For over a year

Sterling served a parish of 1400 people until doctors in London warned him

against the dangers of continuing. On one of these visits to London in

1835 he first met Thomas Carlyle in Mill's office. Hoping for an

appointment to the English chaplaincy in Rome or as an inspector of schools in

the West Indies, Sterling was forced by his health to move with his family to

Bordeaux where for some time he became one of the most celebrated contributors

of poetry and prose to Blackwood's Magazine. This attachment

continued even after a cholera outbreak drove him to return to London, leave his

family with his parents, and spend the winter in Madeira.

In

the aftermath of his Carlyle article, Sterling published several installments of

his translation of Goethe's Dichtung und Wahrheit in Blackwood's

and contributed to Maurice's Educational Magazine, the latter

suggesting that his estrangement from friends in the church was by no means

absolute. He dedicated his collection of poems late in 1839 to his friend

and mentor J. C. Hare, soon to become Archdeacon, and began composing a verse

drama based on the life and death of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford two

hundred years earlier. At this time, too, Sterling began corresponding

with Ralph Waldo Emerson to whom he later dedicated Strafford (1843).

The two enjoyed an instant affinity, both having left the clergy and embarked on

a life of letters.

In

the aftermath of his Carlyle article, Sterling published several installments of

his translation of Goethe's Dichtung und Wahrheit in Blackwood's

and contributed to Maurice's Educational Magazine, the latter

suggesting that his estrangement from friends in the church was by no means

absolute. He dedicated his collection of poems late in 1839 to his friend

and mentor J. C. Hare, soon to become Archdeacon, and began composing a verse

drama based on the life and death of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford two

hundred years earlier. At this time, too, Sterling began corresponding

with Ralph Waldo Emerson to whom he later dedicated Strafford (1843).

The two enjoyed an instant affinity, both having left the clergy and embarked on

a life of letters. her parents' concerns about Sterling's health and his situation outside the

Quaker fellowship. This, too, deadened Sterling's spirits in his long last

winter at Hillside. His bleeding worsened in April and through the summer

he wrote a series of powerful letters to his first-born son in London.

Carlyle describes their last visit together in London and gives examples of

Sterling's letters from these final months. Attended by Mrs. Maurice and

his own brother, Anthony, Sterling died in the night of 18 September 1844.

Carlyle's tribute seven years later at the end of his Life of John Sterling

(1851) is still extraordinarily moving. He was not alone in contemplating

such a tribute of friendship. Mill and Emerson both projected biographies,

and Hare prefixed a long, defensive Memoir to the first volume of his

collection of Sterling's Essays and Tales (2v, 1848). The

so-called religious press had its own objections to Sterling's liberal

tendencies, objections catalyzed by the scandalous suggestion that dinners of

the Sterling Cub omitted the speaking of grace.

her parents' concerns about Sterling's health and his situation outside the

Quaker fellowship. This, too, deadened Sterling's spirits in his long last

winter at Hillside. His bleeding worsened in April and through the summer

he wrote a series of powerful letters to his first-born son in London.

Carlyle describes their last visit together in London and gives examples of

Sterling's letters from these final months. Attended by Mrs. Maurice and

his own brother, Anthony, Sterling died in the night of 18 September 1844.

Carlyle's tribute seven years later at the end of his Life of John Sterling

(1851) is still extraordinarily moving. He was not alone in contemplating

such a tribute of friendship. Mill and Emerson both projected biographies,

and Hare prefixed a long, defensive Memoir to the first volume of his

collection of Sterling's Essays and Tales (2v, 1848). The

so-called religious press had its own objections to Sterling's liberal

tendencies, objections catalyzed by the scandalous suggestion that dinners of

the Sterling Cub omitted the speaking of grace.  "With

Sterling I soon became very intimate, and was more attached to him than I have

ever been to any other man. He was indeed one of the most loveable of men.

His frank, cordial, affectionate and expansive character; a love of truth alike

conspicuous in the highest things and the humblest; a generous and ardent nature

which threw itself with impetuosity into the opinions it adopted, but was as

eager to do justice to the doctrines and the men it was opposed to, as to make

war on what it thought their errors; and an equal devotion to the two cardinal

points of Liberty and Duty, formed a combination of qualities as attractive to

me, as to all others who knew him as well as I did. With his open mind and

heart, he found no difficulty in joining hands with me across the gulf which as

yet divided our opinions."

"With

Sterling I soon became very intimate, and was more attached to him than I have

ever been to any other man. He was indeed one of the most loveable of men.

His frank, cordial, affectionate and expansive character; a love of truth alike

conspicuous in the highest things and the humblest; a generous and ardent nature

which threw itself with impetuosity into the opinions it adopted, but was as

eager to do justice to the doctrines and the men it was opposed to, as to make

war on what it thought their errors; and an equal devotion to the two cardinal

points of Liberty and Duty, formed a combination of qualities as attractive to

me, as to all others who knew him as well as I did. With his open mind and

heart, he found no difficulty in joining hands with me across the gulf which as

yet divided our opinions."