Contact Us

Institutional Communications

Bureau of Mines Building, Room 137

Laramie, WY 82071

Phone: (307) 766-2929

Email: cbaldwin@uwyo.edu

UWs Cheadle Part of Group That Discovered Volcano on Indian Ocean Seafloor

Published October 01, 2020

Michael Cheadle, a UW associate professor of geology and geophysics, examines a rock

sample recovered by a ROV submarine. Cheadle served as a geologist on the German research

vessel R/V Sonne during part of March. The expedition mapped 6,000 miles of the Indian

Ocean seafloor and included the discovery of a large volcano. (Marum, Universitat

Bremen Photo)

Michael Cheadle recently had the opportunity to view a large volcano up close. The novelty is that it was underwater.

Cheadle, a University of Wyoming associate professor in the Department of Geology and Geophysics, was invited to be part of a research expedition that explored part of the seafloor of the Indian Ocean. Cheadle served as a geologist aboard a new German research vessel, called the R/V Sonne.

The research expedition, which took place during March, mapped nearly 6,000 square miles of the seafloor, an area slightly larger than the state of Connecticut, Cheadle says.

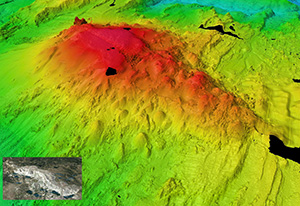

“We discovered a large volcano, which was 18 miles long and 1 mile high,” Cheadle says. “It was interesting because we could clearly see that it was a volcano that exploded, like those we see on the continents, such as Mount St. Helens, for example. But this type of explosive eruption is quite rare at the bottom of the ocean. We named the volcano Mount Mahoney after a famous U.S. geologist who worked on undersea volcanoes.”

During the mapping -- conducted at a resolution of 100 lateral feet -- of some of the least explored seafloor on Earth, Cheadle and other researchers were able to view and study various faults, individual lava flows and volcanic eruption cones in great detail. The group also mapped a “push-up” ridge in a transform fault, which is a fault where two tectonic plates slide past each other, much like the San Andreas Fault.

“This helps us to understand how the Earth’s crust pulls apart at a midocean ridge,” Cheadle explains. “Here, the tectonic plates of the Earth pull apart at a very slow rate and, perhaps, give us an idea of what some of the topography of the Earth will look like when plate tectonics stop many millions of years in the future.”

This sonar image is of Mount Mahoney (in red), a large undersea explosive volcano,

that was mapped by the expedition on the Indian Ocean seafloor. The inset shows the

Snowy Range at the same scale. Mount Mahoney is approximately 29 kilometers long,

compared to the Snowy Range, which is 7 kilometers long. (Koepke, Marum, Universitat

Bremen and Sato Image; inset from Google Earth)

The group named this push-up ridge the Nicolas Ridge, after a famous French geologist. As a matter of scientific protocol, the first people to see some of these features allows them to name the undersea mountain or feature, Cheadle says.

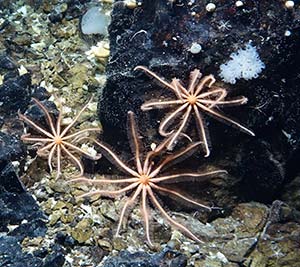

The research group members did not discover any new ocean species they could name, but did spot a number of well-known creatures -- rat-tail fish, sea cucumbers and barnacles -- as well as some very strange creatures such as crinoids, glass sponges, sea spiders and acorn worms.

“There are only about 600 living species of crinoid, but the class was much more abundant and diverse in the past,” Cheadle says. “They really are living fossils, with the first fossil examples found in rocks from 480 million years ago. Contrast that with humans, who have only been around for about the last 6 million years.”

Glass sponges have skeletons made of tiny particles of silica, which is the same material used to make glass. Glass sponges live attached to hard surfaces and consume small bacteria and plankton that they filter from the sea water.

Unlike past expeditions of which Cheadle has been a part, he says no active hydrothermal vents were located. However, the group did find evidence of recent hydrothermal activity. Buoyed by the positive clues, Cheadle says there is a plan to present a funding proposal to the German Science Foundation to go back and search for hydrothermal vents, which are fissures on the seafloor from which superheated water erupts. These vents often support exotic sea life, which may provide clues for the origin of life itself.

To observe the seafloor more closely, the group often used a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) or submarine, named Marum-Quest, that provided video of the seafloor from the ship as well as collected rock samples.

As a geologist, Cheadle’s duties included carrying out the structural analysis of all samples collected on the cruise; overseeing sample recovery from the Marum-Quest; providing commentary on ROV dives, which were broadcast live worldwide; serving as a member of the senior planning team; and conducting several lectures during the short course the group provided to students during the voyage home.

Crinoids (multiarmed creatures) and glass sponges (white colored) on the Indian Ocean

seafloor are viewed from the ROV submarine Marum-Quest. (Marum, Universitat Bremen

Photo)

Researchers aboard the Sonne came from the United States, China, Germany, Italy and the Philippines. The expedition was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research in Germany and the American scientists by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Cheadle, who was funded by NSF, was invited to be part of the research voyage by Jüergen Koepke, a professor in the Institute of Mineralogy at Leibniz University-Hannover in Hannover, Germany. Koepke served as chief scientist during the expedition. Daniel Colwell, a UW master’s student from Nebo, N.C., majoring in geology, is working on the rocks Cheadle collected during the cruise as part of a project, titled “Understanding the End of Plate Tectonics on Earth-Like Planets.” Colwell is currently funded by a Wyoming NASA Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) graduate research fellowship.

This voyage, which departed from South Africa, marked Cheadle’s 10th research expedition and his fifth to the Indian Ocean. The expedition, originally scheduled to run March 6-April 22, was halted March 21 due to COVID-19 developments around the world. While the ship was COVID-free, South Africa closed its ports. Trapped at sea with limited fuel, the research operation was halted, and the vessel sailed to Germany, a trip that took nearly a month, Cheadle says.

“The most exciting part of the expedition is deciding where to explore next,” Cheadle says. “Imagine being the first person to explore the Snowy Range. That’s exactly what it’s like. The scientists decide where the ship goes to map and where to dive with the submarine. So, every day you get a new little part of a map that nobody has seen before, and then there’s the excitement of trying to understand the geology it shows. And, based on that, where to go next.”

For a video of the expedition, in which Cheadle provides some of the narration, go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=PAGh3WrDpyk.

Contact Us

Institutional Communications

Bureau of Mines Building, Room 137

Laramie, WY 82071

Phone: (307) 766-2929

Email: cbaldwin@uwyo.edu