If two or more states want to form a legally binding agreement about sharing or managing water in an interstate river, lake, or aquifer, they can do so through a “Compact” approved by Congress and the states’ legislatures. This makes interstate compacts both federal and state law at the same time. According to the National Center on Interstate Compacts, there are currently 270 compacts in total, covering not only water, but everything from bridges to crime.

Water Apportionment Compacts

Compacts have been formed to manage transboundary waters in a variety of ways, including for pollution control and hydroelectric power. In the West, one type of compact is absolutely necessary—and sometimes contentious. Water apportionment compacts are used to quantify how much water a state can legally use.

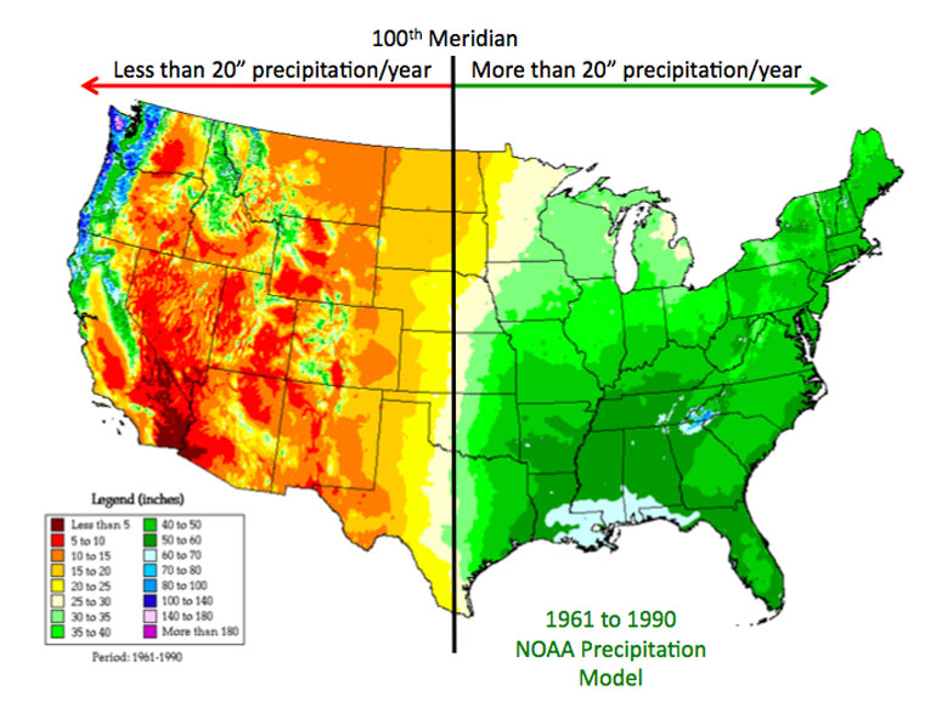

The 100th Meridian, a line of longitude running north to south through the Great Plains, marks the divide between the arid and semi-arid West and the humid East. Water in most of the West comes from snowpack high in the mountains, which serve as natural water towers. When snow melts in the spring, it races downhill toward the sea, nearly always crossing state lines. West of the 100th Meridian, water has shaped settlement patterns, agriculture, and, consequently, the need for cooperative sharing and management of water frequently accomplished by interstate compacts.

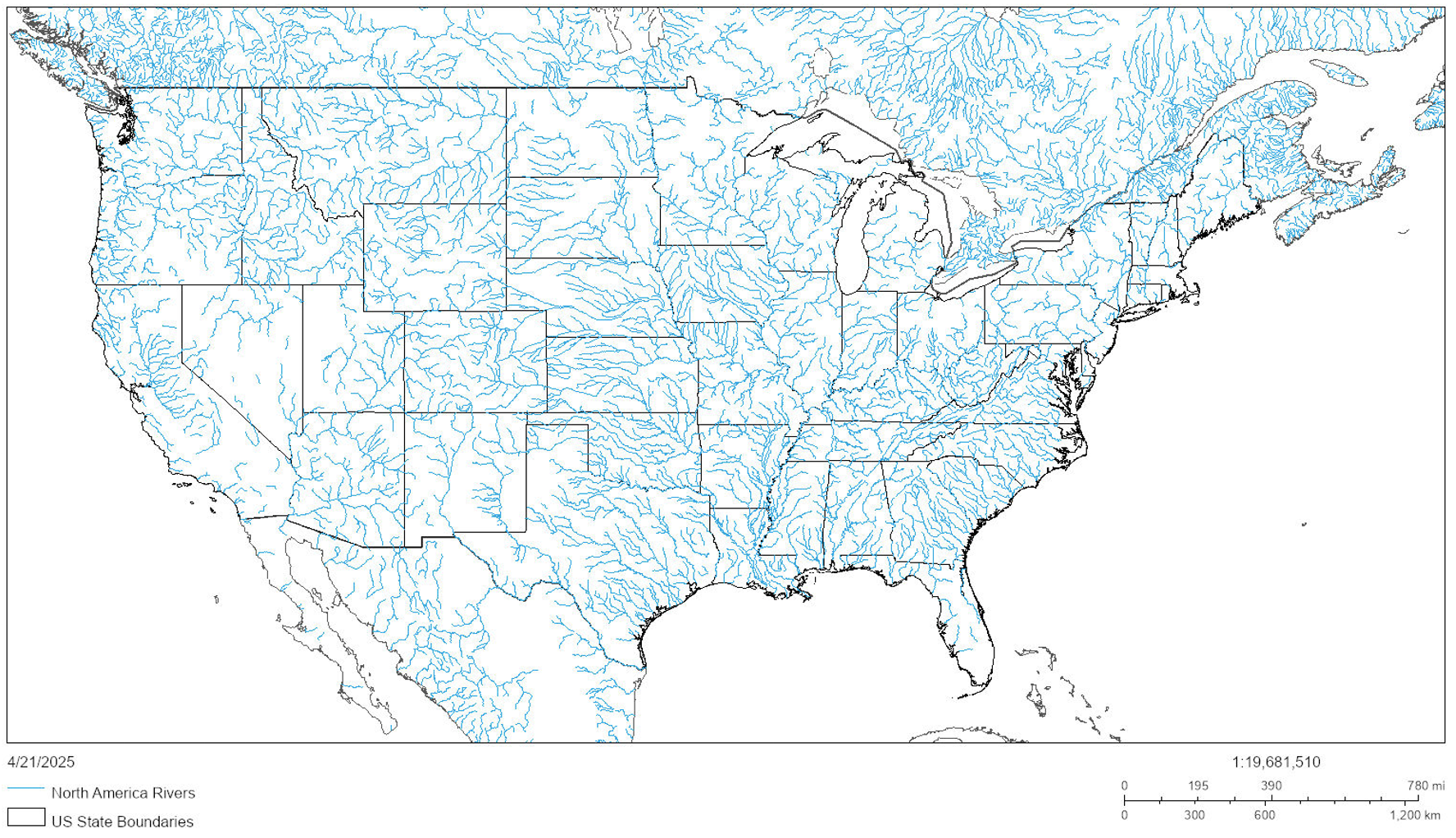

State boundaries are just lines drawn on the landscape. In the West, these lines rarely follow river basin boundaries. You can see for yourself what this looks like.

Due to the disconnect between these lines, not to mention regional water scarcity, interstate cooperation over water is essential to provide stability in the West. There are 23 water apportionment compacts in the region. The following is an interactive map of the compacted basins based on data from the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Click on a compact to learn more about it.

Compact Apportionment & Governance

Water apportionment compacts are like snowflakes in that each one is designed differently. Each of them apportions the use of water in some way, and nearly all of them have some kind of administrative provisions.

How these compacts apportion water use is a major way they are unique from one other. Some compacts use a percentage of a river’s flow, like the Yellowstone River Compact and the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact; others use fixed measurements of water, like the Colorado River Compact; while others, like the Kansas and Oklahoma Arkansas River Compact, put a maximum on allowable sizes of new reservoirs.

But who administers these apportionments? Who enforces them? Who monitors them? To invoke the great lawyerism, it depends.

The governance structures of water apportionment compacts can be broken into three broad categories: (1) a formal commission, (2) no formal commission but administrative provisions, and (3) nothing at all.

Starting with the most complex, formal compact commissions, they are unique like compact apportionments and rarely look identical. Commissions nearly always involve appointed commissioners, from states within the compacted area, who have voting power. A commission’s specific duties are varied. For example, many commissions monitor water use and/or make findings of fact regarding water supplies. As the administrative bodies of these compacts, commissions also sometimes have enforcement powers if a state isn’t complying with an apportionment.

Steamboat Rock in Echo Park, Colorado (subject to the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact and the Colorado River Compact). SOURCE

Many commissions have a single representative per state with one vote, like the Canadian River Compact Commission. Others, like the commission created by the Kansas and Oklahoma Arkansas River Basin Compact, have multiple representatives per state, with each commissioner having one vote. Yet others still, like the commission established by the Red River Compact, have multiple representatives per state, but each state only gets one vote.

Managing transboundary waters can be intense, and conflicts between states are not uncommon, particularly when a basin is in drought. Some compacts, like the Pecos River Compact, have no way for a commission to resolve disputes, relegating the states to suing each other in court. Others, like the Klamath River Basin Compact, have arbitration provisions to resolve disputes internally. Yet others, like the Amended Bear River Compact, allow the commission itself to sue and be sued as a legal entity, apparently enabling the commission to take action against non-compliant states.

Toketee Falls in Oregon (subject to the Klamath River Basin Compact). SOURCE

With the most complex governance structure out of the way, the second category includes compacts that lack a formal commission, but nonetheless contain certain administrative provisions. These compacts utilize state engineers, like in the La Plata River Compact, or gubernatorial appointees, as the Snake River Compact does, for compact administration. They are far more limited in power than commissions, and usually only have barebones powers, such as taking technical flow measurements.

Craters of the Moon National Monument in Idaho (subject to the Snake River Compact). SOURCE

The final governance category is the least complex. Compacts in this category have no formal governance structure or administrative provisions. These compacts are usually small in geographic scope and textual length. The compacted basins are, for whatever reason, deemed too insignificant for formal governance. For example, Goose Lake straddles the border between Oregon and California and its corresponding compact is only 853 words.

Goose Lake in Oregon and California (subject to the Goose Lake Basin Compact). SOURCE

The following is the same map as above but color-coded based on the type of governance structure: (1) green for compacts with a formal commission, (2) orange for compacts without a formal commission but with administrative provisions, and (3) gray for compacts without a formal commission or administrative provisions.

Tribal Nations & Water Apportionment Compacts

In the arid and semi-arid West, water is lifeblood, and its allocation is often complex and contested. The rivers to which water apportionment compacts apply are of interest to three co-sovereigns—not only the states and the federal government, but also tribal nations. Intertwined with the legal frameworks established by water apportionment compacts are the significant, and often senior, water rights held by federally recognized tribes. As of this writing, there are 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, many of which live within compacted basins.

Several classifications of tribal lands fall into compacted basins: (1) reservations, (2) off-reservation trust lands, (3) Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Areas (OTSAs), and (4) State Designated Tribal Statistical Areas (SDTSAs).

Reservations (marked in red on the interactive maps) are most straightforward. Certain states, like California, sometimes call them Rancherias (marked in blue on the interactive maps), while others, like New Mexico, sometimes call them Pueblos (marked in purple on the interactive maps). Sometimes they are also called colonies or communities (marked in gray on the interactive maps), such as the Winnemucca Indian Colony in Nevada. Regardless of these varied names, they are formal land designations made by treaties or treaty substitutes such as statutes and executive orders.

Havasu Falls on the Havasupai Reservation in Arizona (subject to the Colorado River Compact). SOURCE

Off-reservation trust lands (marked in green on the interactive maps) consist of lands that while not located on a reservation, are nonetheless held in trust by the federal government for tribes.

Mariano Lake on Diné (Navajo) Off-Reservation Trust Land in New Mexico (subject to the Colorado River Compact). SOURCE

OTSAs (marked in orange on the interactive maps) are “statistical areas that were identified and delineated by the Census Bureau in consultation with federally recognized [] tribes based in Oklahoma. An OTSA is intended to represent [a] former [] reservation that existed in Indian and Oklahoma territories prior to Oklahoma statehood in 1907.” In most OTSAs, tribal members are subject to tribal jurisdiction instead of Oklahoma’s state jurisdiction. SOURCE

Oologah Lake on the Cherokee OTSA (subject to the Kansas and Oklahoma Arkansas River Compact). SOURCE

SDTSAs (marked in yellow on the interactive maps) are a census designation with less power than OTSAs, as they are not federally recognized. Similar to OTSAs, tribes within some SDTSAs can exercise tribal jurisdiction over their members. The Adai Caddo Indian Nation is a great example in Louisiana. They are a state-recognized tribe, holding no federal reservation or trust lands, and residing instead within the Adai Caddo SDTSA that includes Natchitoches Parish in Louisiana.

Anacoco Lake in the Four Winds Cherokee SDTSA in Louisiana (subject to the Sabine River Compact). SOURCE

Tribal water rights stem from the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1908 Winters decision. While some tribes have had their water rights recognized and quantified, either through adjudication or negotiated settlements, many others have not.

Tribes with water rights on paper often lack infrastructure to enjoy “wet water.”

For example, despite having a quantified water right since 1986, the Ute Mountain

Ute only received funding for a water pipeline from Lake Nighthorse in late 2024,

nearly 40 years later. SOURCE

Lake Nighthorse in Colorado, constructed to provide water to the Ute Mountain Ute and Southern Ute tribes, and the purpose of the Animas La Plata Project. SOURCE

Historically, water apportionment compacts have been negotiated without participation by, or meaningful consultation with, tribal governments. Compact commissions reflect this pattern: no commissions include seats for tribal representatives.

Nearly all water apportionment compacts contain a generic disclaimer regarding tribal water rights. Article VI of the Yellowstone River Compact is a good example:

“Nothing contained in this Compact shall be so construed or interpreted as to affect adversely any rights to the use of the waters of Yellowstone River and its tributaries owned by or for Indians, Indian tribes, and their reservations.”

The Future of Tribes & Water Apportionment Compacts

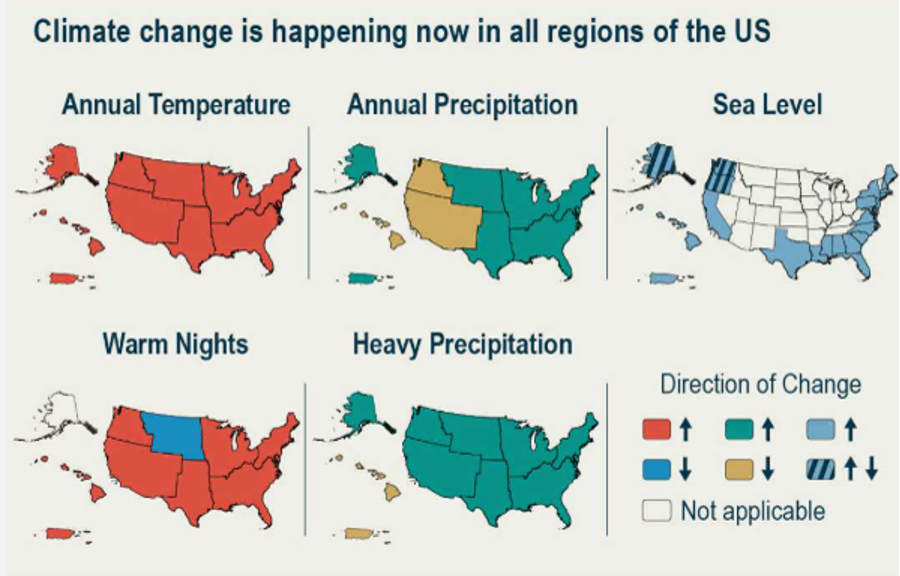

Figure 1.1, Fifth National Climate change Assessment, SOURCE

As the West continues to show signs of getting hotter, there is much potential for future water conflicts, particularly in basins without water apportionment compacts.

In a changing climate, we can expect additional stress on apportionments and water infrastructure. This stress can bleed through to co-sovereign relations and potentially impact tribal sovereignty.

Below is a map of tribal lands located in basins for which water apportionment compacts have not been formed. If new compacts were negotiated in these basins, the apportionments could address tribal water rights in more detail than existing compacts do, and the governance structures could include formal commissions with representatives from all three types of co-sovereigns—federal, state, and tribal. View full screen map »