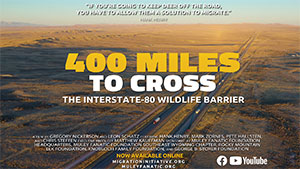

New Film Tells Story of Interstate 80 Wildlife Barrier, Potential Solutions

Published March 27, 2020

It is hard to wrap your head around the big wildlife barrier that cuts across the southern part of Wyoming, but a new investigative film released online this week helps the public see it with fresh eyes.

The 12-minute film, “400 Miles to Cross: The I-80 Wildlife Barrier,” is available on Facebook, YouTube, www.muleyfanatic.org and www.migrationinitiative.org. It shows that Interstate 80 is an almost impenetrable obstacle to movement of pronghorn, mule deer and elk. The highway has severed or truncated migration corridors originating as much as 150 miles away.

The film also makes clear that Wyoming and other Western states have the science and the tools necessary to fix this problem.

The investigation is narrated by Gregory Nickerson, a writer and filmmaker with the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming. In 2019, he set out looking for answers to how the road affects big-game herds.

He teamed up on the project with longtime film collaborator Leon Schatz, a fellow UW alumnus originally from Sheridan.

“The goal of the film was to help Wyoming people see, for the first time, the expansive wildlife barrier that I-80 has become, and to learn what Wyoming can do to reduce the challenges animals are facing,” Nickerson says.

“I’ve met people who say that I-80 is just a whole lot of nothing but, to me, the history of this road and its impact on wildlife is just fascinating,” he adds. “You start to notice places where the elk, deer and pronghorn gather; the trails they make in the snow and along fences; and where they get hit trying to cross.”

Though he had driven the highway for years and seen maps of migrations along the route, the enormity of the problem remained unclear to him.

Interstate 80 runs border to border across 400 miles of southern Wyoming, and it bisects the migration corridors and home ranges of dozens of herds. The interstate interferes with the movement of tens of thousands of pronghorn, mule deer and elk. Over time, barriers to seasonal habitats can decrease the abundance of the herds -- populations that are important to Wyoming’s hunting and tourism industries.

The intersection of human and wildlife routes also has dangerous consequences for people. Hundreds of animals are hit on the road each year, and the wrecks are sometimes fatal for motorists.

Since the interstate was completed in 1970, wildlife researchers have worked to understand how it affects wildlife. Dozens of wildlife studies -- many funded by the Wyoming Department of Transportation (WYDOT) and conducted by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD), industry consultants and UW -- have documented big-game migration routes across nearly all of southern Wyoming.

The resulting map, produced by the University of Oregon InfoGraphics Lab and animated in the film, reveals that the road has effectively severed the vast expanse of wildlife habitat in southern Wyoming. Animals live out their lives either north of I-80 or south of it. Few ever cross.

The Wyoming section of I-80 emerges as an outside laboratory where world-class migrations are intersecting with a nearly impenetrable barrier. Biologists likely know more about wildlife movements in this section of the highway than anywhere else along I-80’s path across the American West.

But all that data can still be abstract without seeing what animals, wildlife managers and highway engineers encounter on the ground. For this reason, the filmmakers went to the field to set up motion-activated wildlife cameras, film aerials with drones and record interviews in windy and snowy conditions.

Nickerson was especially pleased to collaborate on the film with several experts who have worked on the front lines of managing I-80’s impacts on wildlife over decades.

Near Elk Mountain, they interviewed biologist Hank Henry. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Henry did pioneering research with Lorin Ward on how to help mule deer cross under the interstate and reduce highway accidents. They found that migrating deer prefer a wide-open machinery underpass to 10-by-10-foot box culverts.

West of Little America, the film crew caught up with Mark Zornes, wildlife coordinator in Green River for WGFD. Zornes tells the story of a horrific crash in 2017, when a single semitrailer collided with a herd of 25 pronghorn, killing all of them.

Zornes believes building a wildlife overpass would be the most effective way to help pronghorn north of the interstate migrate south to better winter range near Flaming Gorge Reservoir.

Finally, the crew headed to Pinedale to visit with Pete Hallsten, one of the WYDOT engineers who designed the Trappers Point Project. It’s located on a stretch of U.S. Highway 191 in Sublette County that intersects with several pronghorn and mule deer migration corridors.

The Trappers Point Project, completed in 2012, included six underpasses, two overpasses and 12 miles of exclusion fencing. The project virtually eliminated pronghorn mortality on the road and reduced deer collisions by nearly 80 percent. People across Wyoming look to this project as a model for future wildlife-highway improvements.

Hallsten says the project taught him that relationships are vital in making the project happen, particularly among state agencies, biologists, community members and nonprofits. Such collaboration will be necessary for any projects aiming to address I-80’s wildlife issues, he says.

New wildlife crossing designs on I-80 could build on past WGFD and WYDOT successes in places such as Trappers Point, near Pinedale, and Nugget Canyon, near Kemmerer. The lessons of those projects also can help improve past I-80 fencing and underpass projects in areas including “the Sisters,” near Fort Bridger, and Dana Ridge, north of Elk Mountain.

The growing recognition that highways such as I-80 have become barriers to Wyoming's migratory herds prompted WGFD and WYDOT to create the Wyoming Wildlife Roadways Initiative, which identified seven areas along I-80 as targets for wildlife connectivity projects, out of a total of 43 priority opportunity zones across the state.

That effort was a precursor to the new Wildlife Crossing Initiative that the two agencies are now spearheading.

“Creating safe passage for wildlife across Wyoming's highways is a top priority for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department,” Deputy Directory Angela Bruce says. “The Wildlife Crossing Initiative pulls together the expertise of agencies and people who care about wildlife to create safer roadways and provide additional habitat for big game.”

After months of exploring I-80 along the entire length of Wyoming and in the context of the new science of migration, Nickerson says the I-80 wildlife barrier isn’t that difficult of a problem, in terms of conservation challenges.

For perspective, Nickerson notes that the transcontinental railroad was built across Wyoming in two years back in the 1860s, making today’s wildlife crossing projects seem small, inexpensive and feasible by comparison.

“Solving this problem is very doable for Wyoming,” Nickerson says. “We know how to map where the migrations are, where they cross the interstate, and what kinds of crossing structures and fences are needed to get animals flowing again across southern Wyoming.”

What remains is gathering the public will to support the state agencies working to make such projects happen.

Many partners and funders supported the production of the film, including the Muley Fanatic Foundation headquarters and southeast Wyoming chapter, the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, the Knobloch Family Foundation and the George B. Storer Foundation.

The Wyoming Migration Initiative was founded in 2012 at UW to advance the understanding, appreciation and conservation of Wyoming's migratory ungulates by conducting innovative research and sharing scientific information through public outreach.