New UW Documentary Shows People Helping Pronghorn After Devastating Winter

Published April 30, 2025

A new documentary film details how a catastrophic pronghorn die-off influenced the restoration of an estimated 18,000 acres of habitat in Wyoming’s Red Desert.

A GPS-tracking study sparked a collaboration with a rancher in southern Wyoming, resulting in one of the biggest recent conservation successes in Wyoming for the troubled species.

“Unwired: Making Space for Pronghorn in Wyoming's Red Desert” shares how GPS data from the brutal winter of 2022-23 helped partners target 23 miles of problem fencing. The project opened up habitat that has been inaccessible to pronghorn since the 1950s.

The University of Wyoming-produced documentary was released online today (Wednesday) and is viewable at https://thewyldlifefund.org/unwired. “Unwired” earned the Best Film about Wyoming Award at a live premiere at the Wild and Working Lands Film Festival in Laramie March 27, and second place for people’s choice by popular vote of the audience.

The film has particular relevance for Wyoming, which is home to the majority of the world’s pronghorn. Yet even in this stronghold of pronghorn range, productivity is down in these herds, and the statewide population has declined from a peak of 564,580 in 2006 to an estimated 320,000 in 2024. Development and timber encroachment have been cited as contributing to the plight of the pronghorn, while fences and roads are deadly barriers for pronghorn, particularly in extreme winter conditions.

Since the 1960s, biologists have documented how fences and roads contributed to pronghorn winter die-offs in the Red Desert, in projects led by the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, UW, Colorado State University and other agencies.

Mass mortalities occurred during the harsh winters of 1971-73, 1978-79, 1983-84 and 1992-93. Biologists, including Bill Hepworth, Rich Guenzel, Charles Oakley, Elroy Taylor, Greg Hiatt, Jeff Beck, Adele Reinking and Ben Robb, documented the effects of these barriers, while Mary Read and the Bureau of Land Management were instrumental in several prior projects that retrofitted more than 22 miles of fence in 55 locations in 2018 and 2019.

In the context of these past efforts, the film tells a contemporary story of people working to give pronghorn a leg up in the heart of their range. In about a year, biologists used pronghorn movement data to identify barrier fences and help pull together the funding to restore about 28 square miles in total -- which, practically speaking, some professionals consider an overnight success.

Casper native Patrick Rodgers is a filmmaker and research scientist with UW’s Wyoming Migration Initiative and led the film’s production.

“This is really a unique and captivating success story,” Rodgers says. “All of the partners involved in opening up these habitats really deserve a round of applause. It was an honor to tell this story in film.”

The film opens with wintry scenes, flashing to stinging images of pronghorn dead or dying next to woven-wire fences.

“You didn't have to go 20 feet out that fence, and it was just littered with dead pronghorn," says rancher Tom Chant, of NL Land and Livestock, whose family has been ranching in the area for generations. “It was awful. I never want to see that again.”

Chant had a firsthand view of how deep snow forced pronghorn to struggle to find food or shallower areas of snow. Many were trapped against fences as they made desperate escape movements in search of areas with less snow. As a consequence of the once-in-two-decades winter, the pronghorn population in the Red Desert herd unit dropped from 10,800 to just 6,156 animals, well below Game and Fish’s management objective of 15,000.

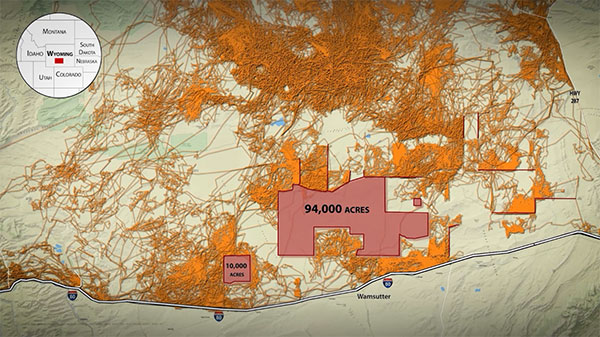

In the winter’s wake, researchers from Western EcoSystems Technology Inc., the Wyoming Migration Initiative and Game and Fish documented an estimated 104,000-acre area -- more than four times the size of the National Elk Refuge in Jackson Hole -- that was largely inaccessible to pronghorn.

Included in that massive area was a 10,000-acre square of land located just north of Tipton. The cause of exclusion was restrictive fencing designs -- primarily woven-wire fencing -- built 75 or more years ago to manage sheep grazing on the checkerboard of public and private lands. During a site visit, Game and Fish identified problem fencing that restricted access for pronghorn to an additional 8,000 acres of adjacent land to the south; however, these fences were not entirely exclusionary.

The team of researchers that mapped the exclusion area was led by Hall Sawyer, a research biologist at Western EcoSystems Technology Inc.

“In contrast to deer and elk that can easily jump over fences, pronghorn prefer to move underneath the fences,” Sawyer says in the film. “And a lot of these fences are woven wire, so pronghorn can’t move underneath them. And then, even some of the four- and five-strand barbed wire fences that have a really low bottom wire, pronghorn can’t move underneath those, either.”

Sawyer and colleague Andrew Telander analyzed data from 45 GPS-collared pronghorn to understand their movement patterns and mortality in the Red Desert. The scale of the exclusion areas came as a surprise.

“We really haven’t seen blocks of habitat unavailable for pronghorn that size anywhere in Wyoming or the West,” Sawyer says. A subsequent analysis of the data recently published in the journal Current Biology found a 3.7-fold increase in mortality due to the compounding effects of fences, roads and snow.

Game and Fish, which initiated the study along with Wyoming Migration Initiative, acted on Sawyer and Telander’s exclusion map by reaching out to the private landowner and the Bureau of Land Management that separately own sections of a 10,000-acre area of checkerboard that were surrounded by exclusionary fences, as well as an additional 8,000 acres of adjacent habitat discovered during the Game and Fish site visit.

“We no longer have sheep,” says Chant, who owns the private acreage within the fences of concern. “My need is to manage cows and a few horses. So, if the fence can accommodate both wildlife and livestock, I was all in,” he says in the film, referring to the prospect of building a new wildlife-friendly fence.

Chant worked closely with Amy Anderson, Game and Fish habitat biologist for the Lander Region, and other partners to organize a project to modify the fences so that pronghorn could move through. Things were coming together quickly, with concerned parties ready to provide financial and logistical support. “I just kept waiting for the other shoe to fall,” Anderson says, but it never did.

“All together, about 23 miles is what was converted … and it took us probably about 45 days,” Chant says. He and his family led the removal of the old fence and the construction of the new design.

The new fence includes smooth bottom wire, so pronghorn can duck under, and top wires with wide spacing for elk and mule deer to jump over without getting tangled. Removable metal rails at corners and intervals along the perimeter can be opened seasonally for wildlife or closed when livestock are present.

The Knobloch Family Foundation, Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, and The WYldlife Fund provided financial support for the fence project.

Chris McBarnes, president of The WYldlife Fund, was instrumental in the fence project’s success and is featured in the film.

“The ‘Unwired’ film masterfully brings the story of the Red Desert pronghorn to life, capturing both their beauty and the challenges they face in their fight for survival,” McBarnes says. “It tells a (true) Wyoming story -- one where cutting-edge research led to swift, effective action thanks to a powerful collaboration between the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, a dedicated private landowner, the Wyoming Wildlife Natural Resource Trust Fund, and generous philanthropic partners.”

Bob Budd is executive director of the Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, a major funder for the Red Desert fence modification.

“This project means a lot because of the magnitude and the vast area that it put back in play for an iconic species,” Budd says. “It’s something that we want to manage and keep in large numbers forever.”

Despite the impressive progress made on a total of 18,000 acres, another roughly 94,000 acres documented in the study remain inaccessible to pronghorn due to woven-wire fencing. An additional 51 miles of fence acts as a barrier to pronghorn movements, which puts the animals at risk in a future where extreme weather events that bring deep and crusted snow are predicted to increase in frequency.

McBarnes hopes the remaining fence will be converted and is actively raising funds for the Red Desert Fence Initiative.

“While there’s still much work ahead to ensure vital habitat connections for these animals, ‘Unwired’ offers an inspiring vision of what’s possible when partnerships and teamwork come together for conservation,” he says.

“Unwired” was produced by the Wyoming Migration Initiative and funded by the Knobloch Family Foundation, with support from The WYldlife Fund and more than 100 individual donors who contributed on UW Giving Day in 2024.

Learn more about the Wyoming Migration Initiative at https://migrationinitiative.org/.

Partners in the Red Desert fence conversion project included The Wyldlife Fund, the Knobloch Family Foundation, Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Partners Program, Wyoming Game and Fish Trust Fund, Muley Fanatic Foundation, Wyoming Governor’s Big Game License Coalition, Little Snake River Conservation District, Bureau of Land Management’s Rawlins Field Office and NL Land and Livestock /Tom Chant.