New Maps Reveal Extensive Pronghorn Migrations Across Northern Sagebrush Steppe

Published November 20, 2025

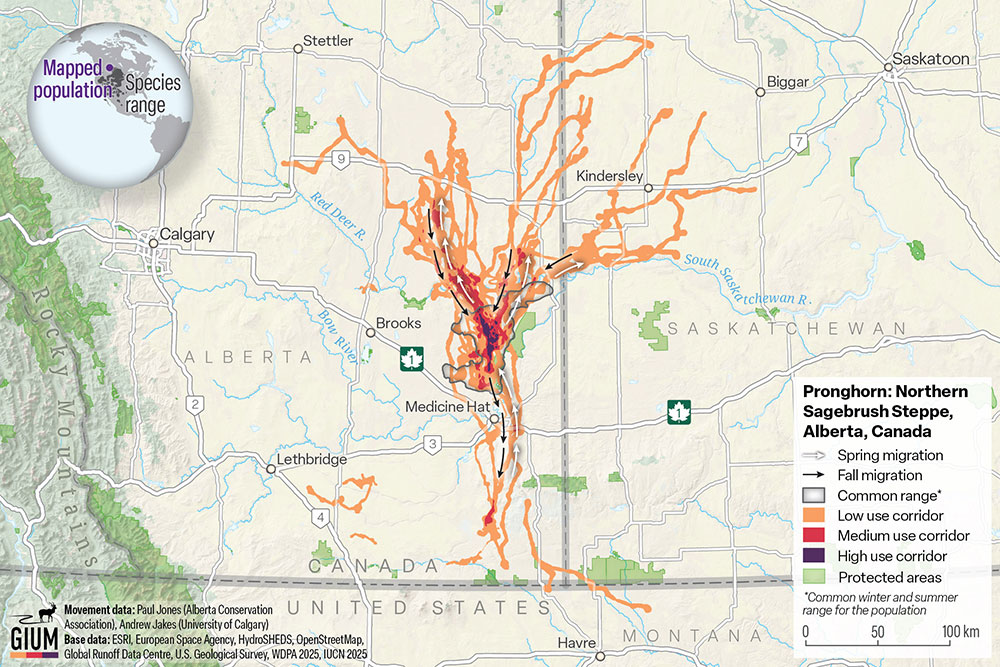

Pronghorn move in one of the migration routes that bisects the Northern Sagebrush Steppe in Montana and Canada. (Paul Jones/Alberta Conservation Association Photo)

In 2004, a female pronghorn made the longest-recorded migration for her species, traveling

from Manyberries, Alberta, Canada, north to her summer range into Saskatchewan and

back for a total distance of 552 miles. She crossed major highways, numerous fences

and provincial boundaries on her trek.

This individual’s journey and many others were captured in new migration maps released

this week documenting two extensive pronghorn migrations in the Northern Sagebrush

Steppe, spanning southern Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada, and northern Montana.

The maps were published in the Atlas of Ungulate Migration, a growing compendium of migration maps depicting ungulate (hooved mammal) populations

around the world.

This work is led by the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration (GIUM), a partnership

of international researchers headquartered at the University of Wyoming that is producing

detailed maps to guide conservation and infrastructure planning to conserve threatened

migrations worldwide.

The first new map depicts pronghorn wintering in Alberta and then traveling to summer

ranges farther north, while the other map shows animals living in the transboundary

region of Saskatchewan and Montana and migrating between the two jurisdictions. Tracking

data indicate that some individuals move between these two migratory systems.

The new maps reveal both the impressive extent of the animals’ seasonal journeys as

well as the intensity of barriers they face on this changing landscape.

Tracking data for the migratory movements occurring in Alberta were provided by Alberta

Conservation Association (ACA), which leads ongoing efforts to monitor and conserve

pronghorn and their habitats. Paul Jones, a wildlife biologist with ACA, was a key

contributor to the maps and author of the associated fact sheets describing the movements

and the challenges pronghorn face.

“Because pronghorn here live at the northern periphery of the species’ range, they

have to be able to migrate sometimes incredibly long distances to escape deep snow

and harsh conditions,” Jones says. “Maintaining a truly connected landscape for migratory

pronghorn is essential to ensuring their populations can thrive.”

Aside from the distance, the migrations depicted in the maps are a true feat considering

how many pronghorn can die attempting to escape winter conditions. Many pronghorn

die because they are unable to crawl under poorly designed fences, and they are increasingly

hit by cars and trains on the major east-west routes.

One of the routes is the Trans-Canada Highway, a major transportation corridor that

bisects the Northern Sagebrush Steppe and impedes pronghorn movements. The Trans Canada,

which is fenced in many sections and is paralleled by a railroad, is a significant

barrier for pronghorn migration.

“There are currently no crossing structures for wildlife on the Trans Canada,” Jones

says. “But using tracking and collision data, the Miistakis Institute, in partnership

with ACA and the Canadian Wildlife Federation, have identified several places where

we can now recommend building over or underpasses.”

Part of the extensive and connected Northern Sagebrush Steppe metapopulation, pronghorn

migrating in southern Saskatchewan and into Montana face similar challenges.

Andrew Jakes, a senior researcher with the Wyoming Migration Initiative and key data

contributor and author for the maps, says that, among the many challenges that linear

features such as fences and roads pose, one of the major unresolved issues for migratory

pronghorn in the Northern Sagebrush Steppe is train collisions.

“Pronghorn are built to outrun predators, but they can’t outrun trains,” Jakes says.

“In my time studying pronghorn, I’ve witnessed several mass winter mortality events

when large groups congregate on railways but are unable to maneuver off and are struck

from oncoming trains.”

In winter 2011, several hundred pronghorn in Montana were killed by trains in a series

of collision events. Attracted to the rail line because it was free of snow, they

didn’t have an easy way to get off the tracks to escape the train. The collisions

were widely reported in regional media and captured the public’s attention, but little

has been done to prevent ongoing train strikes. In 2020, a similar mass mortality

event occurred on a railroad in Saskatchewan.

“We need to find a way to work with railroad companies to mitigate this issue, through

speed regulations or retrofitting, and identify where these common collision sites

are,” Jakes says.

Today, Jones and Jakes are leading new tracking projects to assess pronghorn migrations

across the Northern Sagebrush Steppe, including identification from traditional ecological

knowledge, to gain a more comprehensive picture of what factors are constraining the

animals’ movements and survival. These tracking studies aim to shed light on where

to best direct conservation efforts.

“This landscape is unique in that pronghorn are crossing international and provincial

boundaries, and it will take a lot of work and communication with landowners and continued

planning to make sure it remains permeable for them,” Jakes says. “We believe these

maps can be powerful tools in the effort to conserve pronghorn migrations and identify

mitigation opportunities so that they can move freely and access important seasonal

ranges.”

The atlas provides detailed maps, fact sheets and spatial data so that stakeholders

in the region can incorporate the information into ongoing conservation planning.

This approach -- using detailed maps to guide habitat restoration efforts -- has proven

to be an effective means to advance conservation of ungulate migrations around the

world.

Migration maps and related resources are available through the Atlas of Ungulate Migration, which is implemented under the auspices of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals, a United Nations treaty. View the atlas at www.cms.int/gium.

This is one of the new maps published in the Atlas of Ungulate Migration, a growing compendium of migration maps led by the Global Initiative on Ungulate Migration, a partnership of international researchers headquartered at the University of Wyoming.