Migration Pays Off: Study Links Long-Distance Movement of Mule Deer to Robust Population Growth

Published February 04, 2026

A collared mule deer bounds away from biologists after capture in the Red Desert. She is part of a long-term University of Wyoming study that revealed how migration provides reproductive and nutritional benefits that make migratory mule deer more abundant than resident animals that remain on desert ranges year-round. (Benjamin Kraushaar Photo)

Ungulate migration has fascinated people for millennia. In the Western United States,

ungulates such as elk, bison and mule deer migrate each spring and fall, navigating

snow, predators and human infrastructure.

New research by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and the University of Wyoming, published

this week in Current Biology, reveals that migrating mule deer access more productive summer ranges, have higher

adult survival and raise more offspring compared to resident mule deer that remain

year-round in a desert ecosystem. These findings help explain the burning question

of why ungulates migrate: to find more, and better food.

“This study provides some of the strongest evidence to date on why ungulates need

to migrate across Western landscapes,” says Matthew Kauffman, a USGS researcher at

the Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit based at UW. “Access to forage, fat gained, fawns raised, surviving through harsh

winters -- you name it. The migratory animals did much better than their resident

counterparts.”

The nine-year study followed a portion of the Sublette mule deer herd that spends

the winter in the Red Desert of South-Central Wyoming. Kauffman and others, including

Kevin Monteith from UW’s Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources, captured

more than 200 mule deer at the beginning and end of winter to attach GPS collars and

measure each animal’s body fat, which is a measure of their overall nutritional condition.

They monitored where deer migrated; how many offspring they raised each year; and

when deer died, which allowed them to quantify population growth.

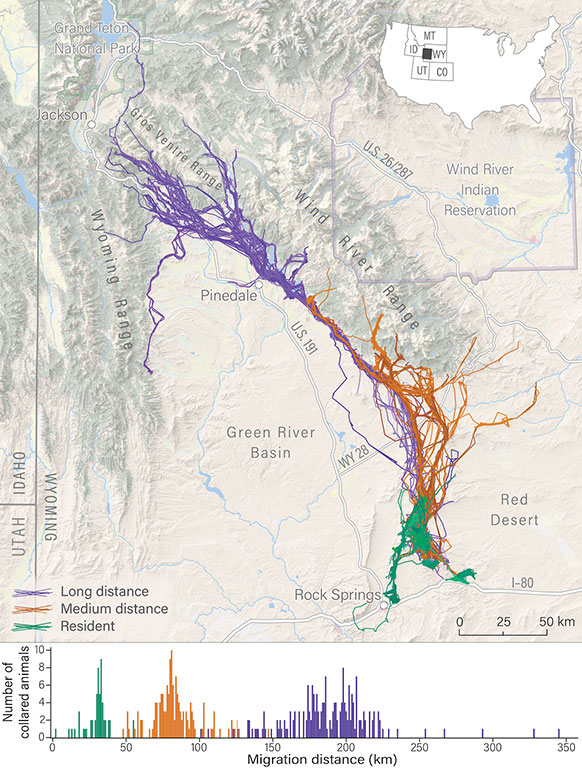

Previous research by the team had documented that mule deer in this herd use three

strategies: Some deer are residents and remain year-round in the desert sagebrush

shrubland, whereas other deer travel mid-distances of 50 miles or longer distances

of 100-plus miles to different summer ranges.

But this new study -- connecting their movement data from the GPS collars to survival,

reproduction and population growth -- provides a rare understanding of how different

migration strategies translate into population performance. Long- and medium-distance

migrants, by traveling to mountainous summer ranges, accessed more nutritious forage

and outperformed residents when the researchers compared fat gain, survival and reproduction

rates.

“But it’s not necessarily the distance of migration. It’s the act of migrating and

obtaining access to more profitable seasonal ranges outside of the desert ecosystem

that allow deer to maintain adult survival and robust population growth,” says the

paper’s lead author Anna Ortega, a UW Ph.D. graduate and now lead researcher at Western

Wildlife Research Collective LLC.

A mule deer doe offers a camera-collar view as she cleans one of her twin fawns in the lush habitat of the Gros Ventre Mountains. The pair is part of the long-distance portion of the Sublette herd that outperforms resident deer that migrate only a short distance in the Red Desert. (Emily Reed-Wyoming Migration Initiative Photo)

Overall, migrants had more body fat than residents, buffering the migrants from extreme

weather: Fatter migrating deer at the beginning of winter had higher survival than

residents during winters with deep snow. Migrants ultimately lived longer than residents

and consistently had more twins.

“Basically, it’s terrible to live in the desert and not migrate,” Ortega says. “It’s

a really difficult -- and unproductive -- lifestyle for these deer.”

The study’s years of demographic data also point to migration allowing deer to be

more resilient in the face of a decade-long drought that has gripped the common landscape

used by all three strategies. While the migrant population continued to show robust

growth despite dry years, the residents’ combination of reduced survival and few offspring

was indicative of a population in decline. In fact, their analyses indicate that residents

could go extinct in 40-50 years -- and this timeline could be accelerated with more

extreme droughts under current climatic conditions.

The long-term study was conducted in collaboration with the Wyoming Game and Fish

Department, as the migration traverses both their Green River and Pinedale regional

offices.

“Since 2016, the agency has had a focus on mapping and protecting migration corridors

across the state,” says Brandon Scurlock with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department’s

Pinedale office. “This study makes it very clear why it is so important to sustain

the migrations Wyoming’s mule deer require.”

The study emphasizes how critical these migrations are for mule deer and other ungulates across the American West. Over 4 million mule deer inhabit the Western United States, but encroaching subdivisions, fencing, roads and energy infrastructure create obstacles that limit or block migrations entirely,” Kauffman says. “It’s a cautionary note for mule deer across the Western United States, most of which are migratory. If we lose those migrations, our Western landscapes will support far fewer deer.”

Mule deer that winter in the Red Desert display three different migration strategies. The long-distance migrants (in purple) have access to the most productive summer ranges that support body fat gain and successful rearing of fawns. This makes their segment more numerous than medium-distance migrants (in orange) and resident deer (in green). (Anna Ortega Credit)