Hands-On Classrooms

Published January 21, 2026

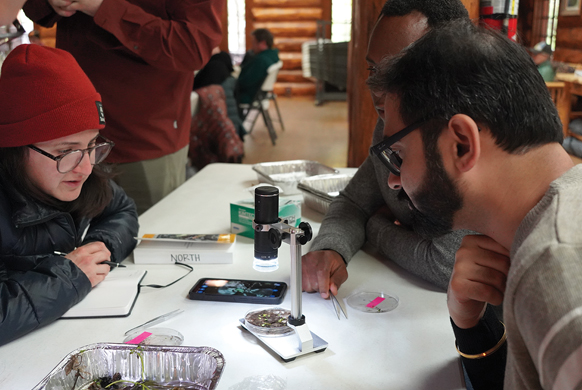

Teachers participate in hands-on learning at LAMP’s Summer Institute. (Photo by Christi Boggs)

Experiential learning takes coursework to the next level.

By Micaela Myers

Experiential learning means learning through doing. It includes internships, study abroad, research, projects and much much more. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, these high-impact practices are linked to multiple indicators of student success, including retention, engagement, graduation rates, career preparation and student success. The more of these experiences students have, the more they benefit.

“When you have a concrete experience, you’re experiencing it with all of your senses,

so it’s literally lighting up and engaging more areas of the brain,” says Rachel Watson,

director of the University of Wyoming Science Initiative’s Learning Actively Mentoring

Program (LAMP), one of several efforts on campus to boost experiential learning. “Students

are having multimodal learning experiences, and they’re also reflecting back on their

learning, which adds to metacognition.”

LAMP trains and supports student teachers, UW faculty and Wyoming community college

faculty in incorporating active-learning techniques and methods into their curricula

during an intensive summer retreat, yearlong workshops and learning communities.

“We’ve trained hundreds of educators across the state,” Watson says.

She adds that experiential learning can happen in online courses as well. Watson recently

partnered with Christi Boggs from UW’s online and digital learning team to launch

the first experiential education online summer institute for faculty. They used the

virtual world Second Life to explore learning environments such as Genome Island and

a virtual DNA lab.

Of course, Watson also incorporates experiential learning into her courses, including

her microbiology capstone course where students are working with the Wyoming Game

and Fish Department and students on the Wind River Indian Reservation. The course

is co-taught by doctoral candidate Erin Bentley and Instructional Professor Liana

Boggs Lynch.

“The schools have been adopting a Trout in the Classroom project where they rear rainbow

trout and release them, and they’ve had some troubles with their tanks around microbiology

and biochemistry, so my UW students are partnering with them to study imbalances in

the tanks,” Watson says.

Senior microbiology student Taylor Erickson of Star Valley, Wyo., says that the students

broke up into groups, studying various hypotheses about what’s causing the trout mortality.

“This class is different because it works with real people in the community to solve

real-world problems,” Erickson says. “Like in life, we are presented with a problem

and a set of observations, and it’s up to us to develop a solution. The class is also

unique in that we must recall or research information on our own to solve problems,

rather than being given all the answers through lectures. I am excited to work on

my group’s project since it is something that we came up with together.”

Visiting Assistant Professor Ashleigh Pilkerton explores Spring Creek with student Aiden Roth.

Honors College Water Course

Aquatic ecologist and visiting Assistant Professor Ashleigh Pilkerton centers her multidisciplinary Honors Water course on experiential learning with field trips, guest speakers and student-led projects about local water issues.

“We explore water through multiple lenses — scientific, historical, cultural, economic

and political — to understand its fundamental role in ecosystems, humanity and the

future of our planet,” Pilkerton says. “The students choose and conduct integrative

learning projects that allow them to research local water-related issues and develop

projects that combine scientific evidence, community context and actionable strategies.”

This year, the students broke up into five groups. The first is researching the psychological

impacts of changes in quality and quantity of water in the Laramie River; the second

is looking at the social, economic and environmental impacts of the new Glade Reservoir;

the third is investigating water waste on campus; the fourth is looking at microplastics

in local waterways; and the fifth group is researching eutrophication, which refers

to the process of nutrient enrichment in a body of water, which can lead to excess

plant growth such as harmful algal blooms.

Sophomore Mo Amelotte of Casper is part of the eutrophication group.

“I’m eager to further understand the effects of eutrophication — and, more importantly,

what we can do to fix such a problem,” says Amelotte, who is double majoring in botany

and honors with a minor in zoology. “However, soft skills and the art of planning

are also important aspects. I’m hoping to learn how to best organize a complex project,

collaborate under pressure, reach out to professionals, share opinions and ideas,

and spread awareness about a serious problem in a manner that encourages hope rather

than panic.”

Amelotte hopes to work in the field of ecology and appreciates the course’s hands-on

approach.

“There is a certain depth of understanding that comes through hands-on and interdisciplinary

experiences,” Amelotte says. “There’s something about actually witnessing an aspect

of a class in real time that adds a dimension of reality and understanding that the

two-dimensional nature of a slideshow can’t achieve. Students will be more likely

to remember a class if they’ve actually experienced it.”

Read student articles from the Honors Water course here.

Students in Associate Professor Alexandra Kelly’s Museology II course visit with Curator of Academic Engagement Alex Ziegler at the UW Art Museum.

Museology II

Across the university, experiential learning is becoming commonplace in all types

of courses, such as history and anthropology Associate Professor Alexandra Kelly’s

Museology II course. This course is cross listed among history, anthropology, American

studies and art and is also part of the museum studies minor.

“The class focuses on real-world museum issues using the repositories around Laramie

— the UW Anthropology Museum, UW Geological Museum, Laramie Plains Museum, American

Heritage Center, UW Museum of Vertebrates and UW Art Museum,” she says.

The class starts with education on museum history, ethics and theory. After field trips to the museums and meeting with the directors to discuss their current issues, students form groups to develop and present proposals.

“I’m always really impressed with what they propose,” Kelly says.

This semester, students are investigating a wide range of topics. These include voices

left out of the historical records such as women noted only by their husbands’ names

at the American Heritage Center, issues regarding private excavation with the Geological

Museum, how to tie the Art Museum’s teaching gallery into the current theme of the

museum’s exhibitions, and developing a policy about collection for the Laramie Plains

Museum.

Kassandra Dutro of Casper took the course as an undergraduate in anthropology with

minors in museum studies and Spanish. She’s now pursuing her master’s degree in anthropology

with an aim to work as a fire archaeologist for federal or state entities.

“Museology II was a great class where I was able to have deeper conversations with

my peers,” Dutro says. “I especially enjoyed visiting all of the repositories and

museums around Laramie where we got to ask working professionals about how they are

responding to challenges. This was important for my future career as an archaeologist

because we do not just excavate cultural material to learn about the past — we also

use professional techniques to care for those objects, to store them in repositories

or museums and to make sure that future generations can learn from them.”

Kelly says hands-on learning makes it real for the students: “They have a stake in

it. I could lecture in class, but actually dealing with specific scenarios provides

a much more meaningful experience.”

Taylor Wagstaff, who used UW’s Science Communications course to take her career to the next level, rolls transect tape in the Wyoming Range. (Courtesy photo)

Science Communication

In her Science Communication course, Department of Zoology and Physiology Associate

Professor of Practice Bethann Merkle teaches science graduate and undergraduate students

key skills using hands-on projects based on issues in their hometowns.

“Communication is the top job skill required in all sectors,” Merkle says. “Yet, most

scientists receive zero formal training in science communication and feel ill-equipped

to share science effectively beyond the academy.”

After an initial research phase, students in her course choose issues in their hometowns

that science could help with.

“They use all the theory and tools from the class to develop a detailed issue report,

to map out the people likely to be affected and then to identify a way that they can

contribute something new to the efforts,” Merkle says.

For example, Taylor Wagstaff conducted an outreach program about mountain lion safety

in Hulett, Wyo., where encounters are common. Seeing the prevalence of bear pamphlets,

Wagstaff decided to put together similar literature on mountain lions and how to handle

encounters, which she presented at the local high school.

“It was very satisfying to be able to take my project into a classroom and interact

with high school students,” Wagstaff says.

After graduating with her degree in wildlife and fisheries biology and management

in 2022, Wagstaff was hired as a lab coordinator in UW’s Monteith Shop and uses skills

she learned in the course. “I have a much broader perspective on what scientific communication

and outreach can look like, which has allowed us to pursue novel outreach and deepen

existing opportunities.”

Senior physiology student Terrin Fauber, who also has a minor in neuroscience, focused his project on fireworks.

“I operate a couple of firework stands in Johnson County during the summer, and during

the 2024 season, we ran into some issues around fire bans being put into effect just

before the Fourth of July, which had a massively negative impact on our sales,” he

says. “To counteract this, I held countless meetings with town officials and other

important members of the community. We eventually agreed that if we could find an

irrigated section of land outside of city limits, we could organize a controlled-shoot

site, where members of the community are allowed to launch any legal fireworks under

the supervision of local firefighters. We found the event to be a massive success,

hosting more than 1,000 people with zero reported fires.”

The project had a lasting impact on the county, which can again use this approach

whenever fire bans are in effect — and on Fauber, who uses these communication and

research skills on a regular basis.

“I have begun to use personally relevant real-world ideas for my class assignments,

which makes projects much more interesting and applicable,” he says. “I just completed

a professional research proposal on chronic stress and its relationship to Alzheimer’s

disease for INBRE funding, and this class was immensely helpful in writing my research

proposal.”