Exploring the Colorado-Big Thompson Project: A Journey Through Colorado’s Vital Water Infrastructure

Colton Goldfarb

Published October 06, 2025

3 Minute Read

Approved in 1937, and constructed between 1938 and 1956, the Colorado-Big Thompson Project (C-BT) is one of the largest infrastructure projects ever undertaken by the Bureau of Reclamation.[1] The project created the largest trans-basin water diversion project in Colorado.[2] Consisting of over 100 structures, the C-BT provides Colorado’s heavily populated Front Range with a large portion of its water.[3] The Western Slope collection system captures water from the headwaters of the Colorado River through a series of dams and conveys the water to the Front Range through the Alva B. Adams Tunnel.[4] Historically, the project has supplied the Front Range with 215,000-acre feet of water annually, with deliveries to twenty-nine communities and 120 irrigation ditches irrigating 650,000 acres of farmland.[5]

Recently, I accompanied Professor Jason Robison and five classmates to this vital infrastructure and the Colorado River’s headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park, as part of Colorado River Seminar at the University of Wyoming College of Law. We got a first-hand look at the size and scale of the C-BT and the reliance western communities have on the Colorado River. Starting at Granby Dam, we viewed the major impoundment of the Colorado River constructed between 1941 and 1950.[6] Lake Granby serves as a holding station for water waiting to be diverted to Front Range users.[7]

Just above Lake Granby, we visited Shadow Mountain Reservoir. Constructed between 1944 and 1946, it is an extension of Grand Lake and another holding site for water to be diverted to the Front Range.[8] Connected by a short canal built by the Bureau of Reclamation, Shadow Mountain Reservoir leads into Colorado largest natural lake, Grand Lake.[9] Today, Grand Lake serves as the main holding site for water to be diverted to the Front Range. The beautiful lake sits nestled between high-mountain peaks and was carved by glaciers 30,000 years ago.

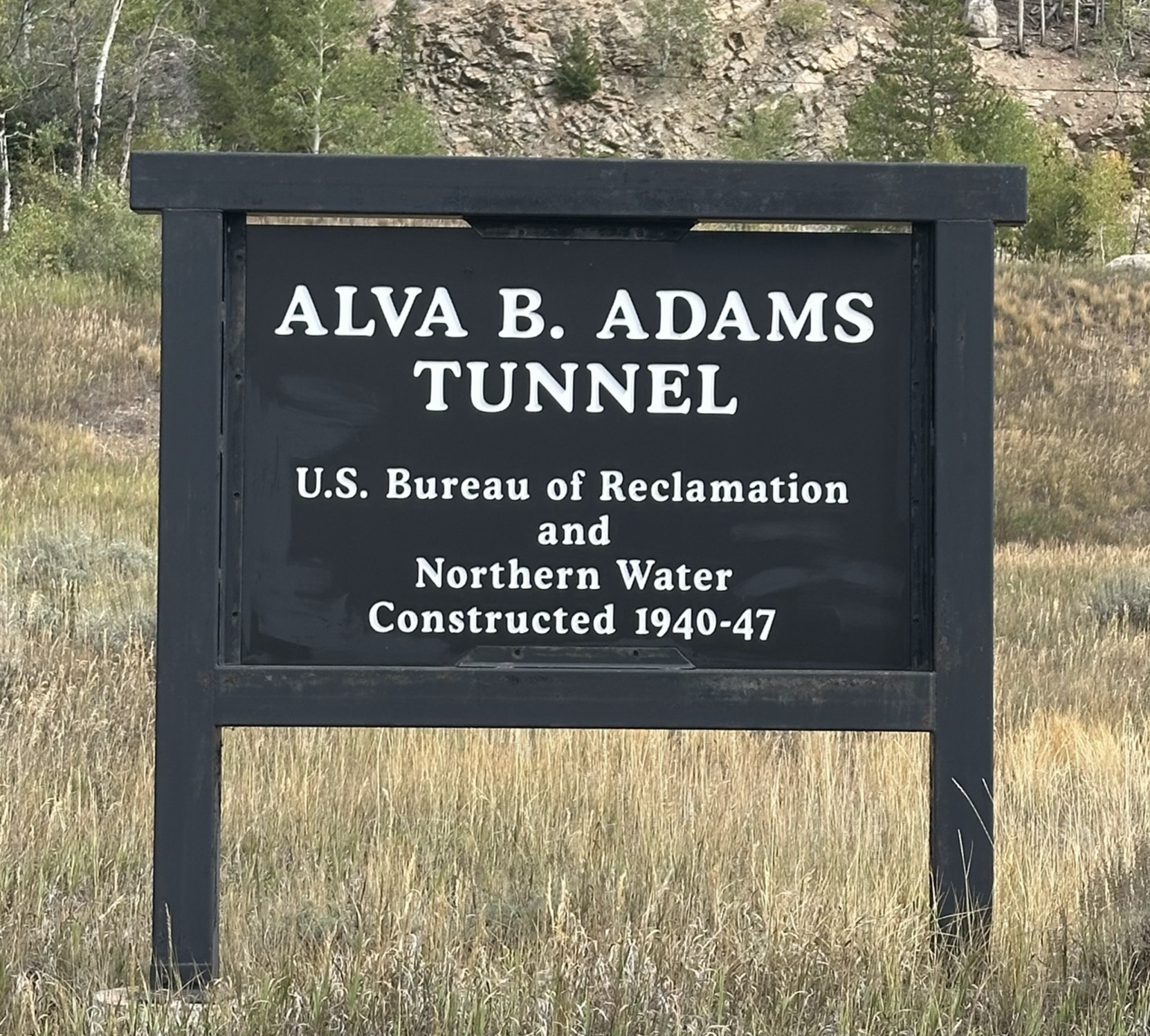

The Alva. B. Adams Tunnel, built between 1940 and 1947, is located on Grand Lake’s eastern shore.[10] The tunnel cuts 13.1 miles through the Rocky Mountains and carries up to 550 cubic feet per second (cfs) of water at any given time.[11] Named for U.S. Senator Alva B. Adams, a key advocate in the C-BT’s development, the tunnel is a symbol of the crucial role Colorado River water plays in the western United States.[12] While visiting the western portal of the tunnel, we were able to grasp the Front Range’s dependence on Colorado River water and the historical tension between Western Slope communities and the Front Range. The aridity of the West has led to reliance on the Colorado River from its headwaters above Grand Lake to its delta in northern Mexico. This reliance has prompted communities, like those along Colorado’s Front Range, to engage in contentious out-of-basin water transfers like the C-BT.

After the tour of the C-BT infrastructure, we camped in the Kawuneeche Valley of Rocky Mountain National Park. Serenaded by the bugles of rutting elk, we rested before embarking the next morning on a hike to the Colorado River’s headwaters at La Poudre Pass. The second day of the field trip was misty, with rain clouds slipping into the valley from the high peaks above. The Colorado River Headwater Trail zig zags through forests and meadows with lush foliage and plentiful wildlife. The Colorado River, at this point in its journey, is no more than ten feet across and ankle deep in most places. Its crystal-clear icy waters are nothing like the desert hues found in its downstream paths across the Colorado Plateau. It is a far cry from the mighty river that cuts through the Grand Canyon and sits behind the colossal Hoover Dam. To read about that is one thing, but to see the small scale of the river that is the lifeblood of the American West, “America’s Nile,” is truly immersive.

At the old site of Lulu City, an abandoned mining town along the river, we witnessed the Colorado River in its minimal state and the hydrological cycles of rain and snow that create it. Professor Robison noted that walking through the rain on the hike was like walking through the river itself, as all rivers start in the clouds—perfect rhetoric to understand the significance and power of the place under our hiking boots. Upon returning to the College of Law in Laramie, participants in this epic excursion had formed a deeper connection to and understanding of the Colorado River, and the “Law of the River” controlling its management, as we continue through the seminar and our future endeavors.

[1] Colorado-Big Thompson Project, U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION, https://www.usbr.gov/projects/index.php?id=432 (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[2] Colorado-Big Thompson Project, COLO. ENCYCLOPEDIA, https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/article/colorado-big-thompson-project (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] Granby Dam, U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION, https://www.usbr.gov/projects/index.php?id=291 (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[7] Id.

[8] Shadow Mountain Dam, U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION, https://www.usbr.gov/projects/index.php?id=235 (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[9] Grand Lake, Colorado-Big Thompson Project: Reservoirs and Lakes, NORTHERN WATER, https://www.northernwater.org/water/projects/colorado-big-thompson-project/reservoirs-and-lakes/grand-lake (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[10] C-BT Infrastructure, NORTHERN WATER, https://www.northernwater.org/water/projects/colorado-big-thompsonproject/cbt-infrastructure (last visited Sept. 24, 2025).

[11] Id.

[12] Id.