The Long Road to Rescinding the Roadless Rule

Bethany C. Aragon

14 Minute Read

On June 23, 2025, during a meeting of the Western Governors’ Association, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced the Department’s intent to rescind the 2001 Roadless Area Conservation Rule.[i] Citing President Trump’s Executive Order 14192, Unleashing Prosperity Through Deregulation, Secretary Rollins stated that the proposed rescission would align with the administration’s priorities by enabling more effective wildfire prevention through local forest management, and economic development through “responsible timber production.”[ii] The move also supports President Trump’s March 1, 2025, Presidential Memorandum directing agencies to take immediate action to expand domestic timber production on federal lands.[iii]

However, rescinding a federal rule is a legally complex and time-consuming process. Under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), executive agencies like the Department of Agriculture (USDA) generally must engage in a full notice-and-comment rulemaking process, which can take up to a year or more.[iv] For context, the original Roadless Rule took more than 15 months to finalize—from its initial notice of intent in October 1999 to its adoption in January 2001—and generated more than 1.6 million comments.[v] While the APA contains a narrow “good cause” exception that allows agencies to forgo notice-and-comment rulemaking when procedures would be “impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest,” courts generally interpret this exemption narrowly.[vi] Given the complex legal history of the Roadless Rule, substantial public engagement, and the rule’s overlap with other federal and state land management frameworks, invoking “good cause” would likely provoke litigation and be difficult to justify. Therefore, a similarly drawn-out process is likely if the agency moves forward with rescission, especially given the environmental, economic, and political stakes involved.

In the meantime, states have an opportunity to lead by establishing their own protections. Idaho and Colorado have already established their own Roadless Rules, tailored to the unique ecological and economic conditions of each state.[vii] Their experience suggests a viable path forward: that local control can offer more flexible, targeted management while maintaining core conservation goals.[viii] Whether this model will be adopted more widely remains to be seen—but with the agency facing a long road to rescission, it may be the most pragmatic option available for states seeking to retain protections within their inventoried roadless areas.

I. Background: What is the Roadless Rule and Why Was It Created?

In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.[ix]

The Wilderness Act of 1964, which has now set aside a total of 111.7 million acres in over 803 wilderness areas[x]—36 million of which fall under Forest Service management—also set the stage for decades of debate over how to classify the agency’s remaining 193 million acres of public lands.[xi] By 1977, the Forest Service had finalized two “Roadless Area Review and Evaluation” studies to identify and categorize roadless and undeveloped lands in the National Forest System.[xii] These studies aimed to determine whether such lands should be recommended for wilderness designation or managed for other forms of development and use.

In response to Congressional mandates under the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 and the National Forest Management Act of 1976, the Forest Service’s Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) II study proposed allocating 62 million acres into three categories of uses: designated wilderness, nonwilderness (available for activities such as timber harvest and road construction), and “further planning” areas requiring more study.[xiii] The debate over how to manage these inventoried roadless areas continued into the 1980s and 1990s, culminating near the end of President Clinton’s administration with a memorandum directing the Secretary of Agriculture to initiate protections for roadless areas.[xiv] A week later, the USDA issued the Notice of Intent and, following extensive public comment and environmental review, the Roadless Area Conservation Rule was adopted on January 12, 2001.[xv]

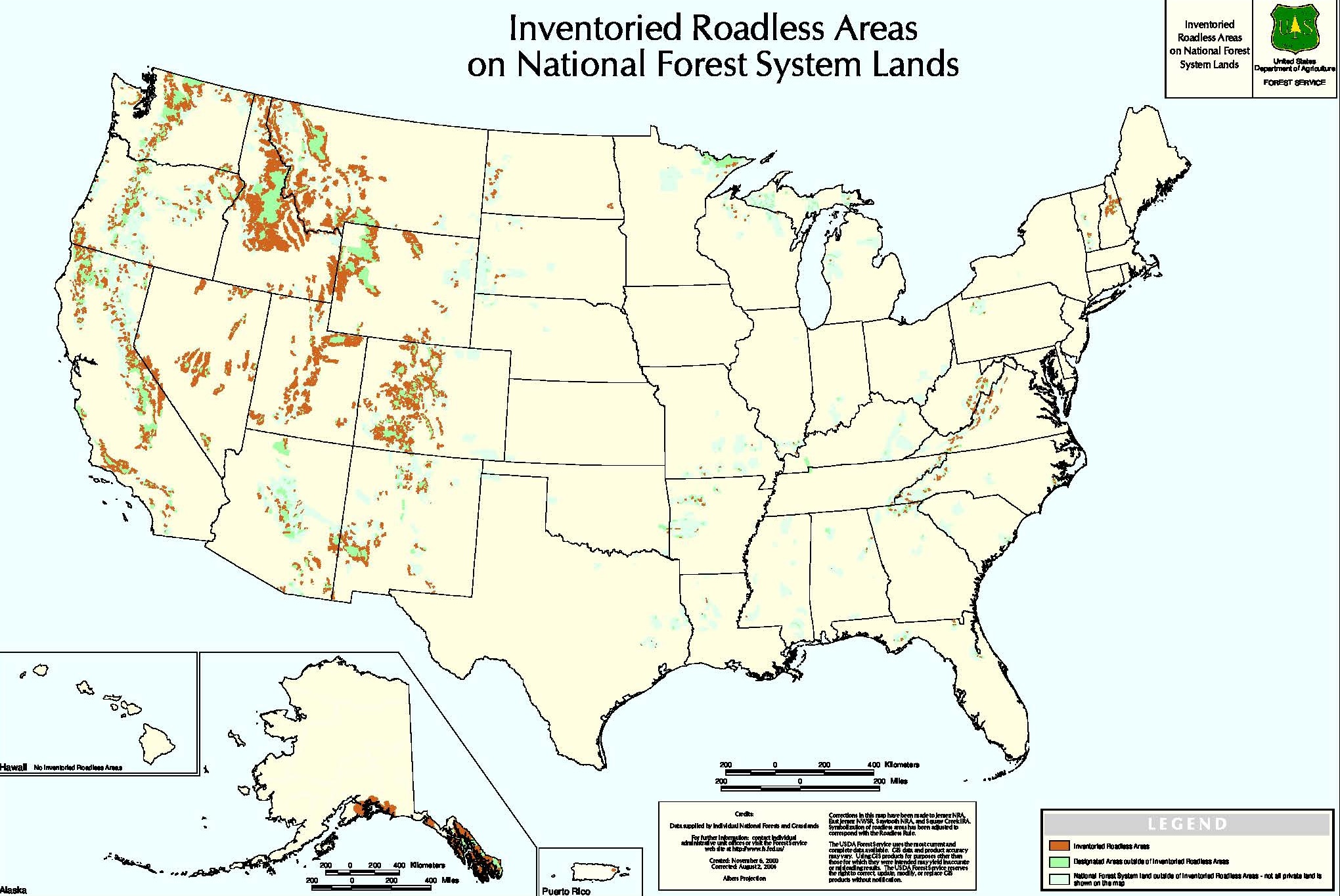

The Roadless Rule’s stated purpose is to “provide, within the context of multiple-use management, lasting protection for inventoried roadless areas within the National Forest System.”[xvi] It prohibits most road construction, road reconstruction, and timber harvesting within Forest Service inventoried roadless areas.[xvii]

Today, the Roadless Rule remains one of the most significant federal regulations governing public land conservation. Its sweeping protections apply to nearly 58.5 million acres across 39 states and have withstood decades of legal and political challenges.[xviii] Any attempt to rescind or revise the rule must contend not only with its legal underpinnings but also with its legacy of public engagement, ecological research, and significance to other key environmental regulations.[xix]

II. The Case for Rescission: Wildfire Mitigation and Economic Development

While the Roadless Rule has withstood multiple legal and political challenges since 2001, opposition to it has remained steady—particularly among western states with large tracts of federal land designated as inventoried roadless areas.[xx] Many of the concerns raised during the original rulemaking process are still central to the current push for rescission. According to a broad coalition of Western lawmakers, state officials, and land managers, the rule has increased wildfire risk, curtailed economic opportunity, and obstructed access to public lands and infrastructure.[xxi]

More Fire, Less Management

One of the most common criticisms of the Roadless Rule is that it has hampered effective wildfire mitigation by adopting a policy of “protection through inaction.”[xxii] By restricting access to roadless areas, the rule has made it more difficult to thin overstocked forests, conduct prescribed burns, or respond quickly to wildfires. Representative and former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, R-Mont., summed up the concern succinctly: “If you can’t build a road, you can’t fight fires, you can’t cut trees, and you can’t properly take care of our national heritage held in our public lands.”[xxiii]

The American Forest Resource Council (AFRC) reports that since the Roadless Rule was adopted, over 36 million acres of National Forest System lands—including 8 million acres of inventoried roadless area—have burned.[xxiv] Supporters of rescission argue that modern forest conditions shaped by prolonged drought, insect outbreaks, invasive species, and climate change require flexible and proactive management strategies that the Roadless Rule restricts.[xxv] A key tenet of forest fire prevention is limiting the spread of fires once ignited, which requires investment in infrastructure—such as access roads, tracks, and firebreaks—according to the Forest Fire Priority Action Plan.[xxvi] Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz argues that the Roadless Rule has hindered such investment: “For nearly 25 years, this rule has frustrated land managers and served as a barrier to action—prohibiting road construction which has limited wildfire suppression and timber harvesting on nearly 60 million acres. The rule has trapped [inventoried roadless areas] in a cycle of neglect and devastation.”[xxvii]

Economic Opportunity Lost

Critics of the Roadless Rule also argue that it has blocked access to timber, minerals, and renewable energy resources, stifling economic growth in rural communities.[xxviii] Senator Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, stated that the rule has “hindered Alaskans’ ability to responsibly harvest timber, develop minerals, connect communities, or build energy projects at lower costs—including renewable energy projects like hydropower.”[xxix] Similarly, Representative Doug LaMalfa, R-Cal., noted that the rule has resulted in “more overgrown forests, more catastrophic wildfires, and fewer jobs in rural counties that rely on active forest work to sustain their economies.”[xxx] Supporters of the rescission also point to emerging markets like woody biomass, mass timber, and sustainable aviation fuel as forest-based opportunities that remain largely out of reach due to the Roadless Rule’s blanket restrictions.[xxxi]

Limited Access to Lands and Infrastructure

Another long-standing critique of the Roadless Rule is its impact on access. In the “checkerboarded West,” where private, public, and tribal lands are interspersed, the rule’s prohibition on road construction and reconstruction can obstruct access for those with reserved or outstanding rights.[xxxii] It has also been criticized for limiting public use by hunters, anglers, and recreationists, and said to make it more difficult for first responders and utility crews to maintain or repair critical infrastructure—such as powerlines, pipelines, and dams—located within inventoried roadless areas.[xxxiii]

Supporters of the rescission also emphasize that many of these areas are not truly pristine and were not intended to be “de facto wilderness areas.”[xxxiv] Instead, they are “roaded roadless” areas—already impacted by development but still subject to the rule’s prohibitions.[xxxv] The result, they argue, is a misapplication of conservation tools to lands that may be better suited for multiple-use management.[xxxvi]

Risks to Watersheds and Drinking Water

According to Secretary Rollins’ opinion piece in the Deseret News, the Roadless Rule has failed to protect drinking water.[xxxvii] Unmanaged forests in roadless areas—28 million acres of which are at “high or very high risk of catastrophic wildfire” according to Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz[xxxviii]—pose growing threats to municipal watersheds because high-severity wildfires increase sediment runoff into reservoirs, which in turn threatens drinking water supplies for downstream communities.[xxxix] Proponents of rescission argue that without the ability to actively manage these areas, the risk to public health and water infrastructure will only increase.[xl]

A Path Toward Local Control and Stewardship

For many western officials, rescinding the Roadless Rule is not about deregulation—it’s about restoring local control. Senator John Hoeven, R-N.D., called the move “an important step in helping to ensure access to the grasslands and putting decision-making back into the hands of locals who know best how to manage these lands.”[xli] In the same spirit, Wyoming’s at-large representative Harriet Hageman called the rule “an outdated policy [that] has long hindered effective forest management” and praised USDA’s efforts to work with stakeholders to “create jobs and preserve resources vital to our way of life.”[xlii]

Wyoming State Forester Kelly Norris emphasized the need for consistency. Several national forests in Wyoming, including Bridger-Teton, Bighorn, and Medicine Bow-Routt, still operate under land-use plans that predate the 2001 rule.[xliii] Removing the roadless designation would eliminate conflicts between these plans and the Roadless Rule’s overlay, allowing for clearer, more coordinated forest management within the state.[xliv]

Not a Free-for-All

Supporters of rescission are quick to clarify what rescission would not do. Repealing the Roadless Rule would not eliminate environmental protections like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) or the Endangered Species Act (ESA).[xlv] As the AFRC put it, “Rescinding the rule does not upend environmental laws like the National Environmental Policy Act or the Endangered Species Act. [W]e are supportive of reforms that modernize stewardship and give public land managers the tools they need to restore the health and resilience of these forests before we lose more of them.”[xlvi]

In short, the case for rescission is grounded in a desire for more nuanced, locally informed land management that balances conservation with access, public safety, and economic opportunity. Whether the recission of the Roadless Rule—and whatever replaces it—will achieve those outcomes, remains to be seen.

III. The Case Against: Ecological, Legal, and Procedural Concerns

When President Clinton directed his secretary of agriculture to develop protections for America’s roadless national forest lands in 2000, he drew inspiration from President Theodore Roosevelt’s foundational commitment to conservation and his belief that one of America’s principal duties is “leaving this land even a better land for our descendants than it is for us.”[xlvii] President Clinton acknowledged, however, that we have often failed in our duty and “too often, we have favored resource extraction over conservation, degrading our forests and the critical natural values they sustain.”[xlviii] The Roadless Rule, he argued, was a necessary course correction—reflecting a growing desire among the American public to “restore balance to their forests.”[xlix] Opponents of rescission argue that it is that balance that is now at risk.

Roads and Logging Don’t Prevent Wildfires

One of the central justifications for rescinding the Roadless Rule is wildfire prevention—but many fire scientists and conservationists challenge this premise. In her official statement regarding the proposed rescission, Rachael Hamby, Policy Director for the Center for Western Priorities, stated that “[c]ommercial logging exacerbates climate change, increasing the intensity of wildfires.”[l] Studies have shown that timber harvesting often leads to homogenous forested areas that will then burn at a more uniform, sustained high intensity.[li] Instead of more roads and logging, opponents of rescission call for smarter planning around the wildland–urban interface, increased use of prescribed burns, and rethinking fire as a natural and necessary ecological force.[lii]

Environmental Rollback, Not Reform

Opponents see the rescission as a broad attack on clean air and water protections, wildlife habitat, and biodiversity.[liii] Peggie DePasquale of Wyoming Wilderness Association stated that “[c]lean water, clean air, healthy wildlife populations and opportunity to escape into pristine landscapes that aren’t crisscrossed by roads are all characteristics that define Wyoming, and are all characteristics we stand to lose with the rescission.”[liv] Similarly, the Wilderness Society opposes the rescission, noting that opening inventoried roadless areas to road construction and timber harvest undermines decades of environmental gains and threatens to accelerate climate change.[lv] Critics also argue that the move would benefit a narrow set of industrial stakeholders—particularly the timber and extractive industries—at the expense of long-term ecosystem health and forest conservation.[lvi]

Complex Rules, Interconnected Systems

Since 2001, the Roadless Rule has become deeply embedded within a broader network of environmental and land management policies. It intersects with the Endangered Species Act, state hunting and fishing regulations, motorized vehicle access rules, and long-term forest planning documents.[lvii] Opponents, such as University of Montana public lands scholar, Martin Nie, warn that rescinding the rule without accounting for its integration across these systems could lead to administrative confusion—and likely litigation.[lviii] As Nie put it, “[r]emove that protection and watch the game of Jenga come crashing down.”[lix]

Tailoring, Not Trashing

Critics also reject the idea that rescission is the only solution for modernizing forest management. Instead, they point to the successful state-specific roadless rules adopted by Idaho (2008) and Colorado (2012).[lx] Those rules were developed through extensive public input and reflect each state’s unique environmental and economic needs.[lxi] Rather than repealing the national rule outright, opponents suggest allowing governors to propose amendments or exceptions to address specific management challenges—preserving the core protections while adapting at the margins.[lxii]

Minimal Benefit, Maximum Risk

Many inventoried roadless areas may offer limited economic value and would require costly development and ongoing maintenance. As Mary Erickson, former supervisor of the Custer Gallatin National Forest in Montana, observed, “[a] lot of roadless lands are roadless for a reason. They’re steep and rugged and don’t necessarily have high-value timber.”[lxiii] Erickson also notes that existing accessible forest stock may be sufficient to meet the administration’s goal of increasing timber harvest by 25%, without compromising the integrity of protected roadless areas.[lxiv] In that light, rescission may fall short of delivering the rural economic development its proponents anticipate.

While many western officials have voiced support for rescinding the Roadless Rule, others remain firmly opposed. New Mexico’s Democratic governor, Michelle Lujan Grisham, for example, publicly defended the rule at the Western Governors’ Association meeting where Secretary Rollins announced the USDA’s intent to rescind it.[lxv] At the federal level, Oregon Representative Andrea Salinas, D-Or., reintroduced the Roadless Area Conservation Act in June 2025 in an attempt to codify protections for inventoried roadless areas and shield them from future administrative rollbacks.[lxvi]

These responses underscore how deeply contested the Roadless Rule remains—politically, ecologically, and procedurally. A 2019 Pew Charitable Trusts survey found that 75% of Americans support the Roadless Rule, and that support spans political groups and the rural-urban divide.[lxvii] As the debate continues, any attempt to rescind the rule will have to contend with this broad public support—resistance that is likely to translate into a protracted and complex federal rulemaking process.

IV. How Federal Rule Making Works: The Road Ahead

If history is a guide, then rescinding the Roadless Rule will be anything but quick. The original 2001 Rule took more than 15 months from start to finish, beginning with a Notice of Intent in October 1999 and culminating in a Final Rule published on January 12, 2001.[lxviii] That process was preceded by an 18-month Interim Rule suspending road construction in inventoried roadless areas, during which the Forest Service received more than 119,000 public comments urging permanent protections.[lxix] When the agency formally proposed the Roadless Rule on May 10, 2000—alongside a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS)—it ultimately received a staggering 1.6 million comments before issuing the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) that November.[lxx] Given that precedent, rescinding the rule now will likely require an equally rigorous and time-consuming process.

According to the USDA and Forest Service, repealing the Roadless Rule will involve a three-stage process under the Administrative Procedure Act.[lxxi] First, the agency will publish an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) in the Federal Register to solicit early public input.[lxxii] This will be followed by a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM), which outlines the agency’s intentions and opens a formal public comment period.[lxxiii] After reviewing and adjudicating comments, the agency may issue a Final Rule—or decide to revise or withdraw the proposal entirely.[lxxiv] In addition to this procedural roadmap, the rescission effort must comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), including the preparation of both a DEIS and FEIS.[lxxv] The agency must also conduct tribal consultations, coordinate with affected states, and ensure compliance with the Endangered Species Act.[lxxvi] All told, the process will likely take well over a year—and is almost certain to draw intense public scrutiny and legal challenge.

V. What Happens to State Roadless Rules in Idaho and Colorado?

While Secretary Rollins’ announcement signals change at the federal level, states like Idaho and Colorado have already charted their own paths—and are largely insulated from any impacts of the federal Roadless Rule rescission.

Idaho: A State-Specific Roadless Rule

Idaho, which ranks second only to Alaska in acres designated as inventoried roadless

areas, was the first state to develop its own alternative to the 2001 federal Roadless

Rule. Then-Governor (now Senator) Jim Risch initiated the process in 2006, and the

Idaho Roadless Rule was finalized in 2008.[lxxvii] It now safeguards approximately 9.3 million acres of roadless lands under a state-specific

management framework.[lxxviii]

Designed to reflect Idaho’s unique landscape and local priorities, the rule accommodates a range of uses while still maintaining core conservation principles. Though challenged early on, the Idaho rule has since gained broad, bipartisan support from policymakers, Native American tribes, industry stakeholders, and conservation groups alike.[lxxix] Crucially, it remains independent of any federal regulation, demonstrating how states can craft lasting, flexible forest protections tailored to local needs.[lxxx]

Colorado: Another Model for State Autonomy

In 2012, after years of bipartisan collaboration and public input, Colorado adopted

its own Roadless Rule to protect its roughly 4.2 million acres of inventoried roadless

areas.[lxxxi] Like Idaho’s, Colorado’s rule remains in effect and insulated from rescission of

the federal Roadless Rule.[lxxxii] Following Secretary Rollins’ announcement, Governor Jared Polis reaffirmed that the

state’s protections would stay intact—setting a strong example of how state-level

policymaking can serve as a buffer in times of federal policy shifts.[lxxxiii]

Why State Rules Matter

Local tailoring: State rules can be designed to accommodate each region’s unique ecological conditions, economic priorities, and stakeholder needs.

Resilience to federal change: Even if the federal rule is rescinded, state-specific rules remain binding—continuing to govern road construction and timber harvest in inventoried roadless areas.

Blueprint for other states: Colorado and Idaho demonstrate how state-driven strategies can provide both conservation security and flexibility in managing public forest resources.

VI. Conclusion

Given the time and effort it took to adopt the original Roadless Rule—15 months, over 1.6 million public comments, and extensive agency coordination—rescinding it will not be quick or simple. The current debate reveals deep and valid concerns on both sides, from wildfire mitigation and economic access to habitat protection and climate resilience. What’s clear is that any rescission effort will be legally and politically fraught, and litigation is almost certain.

For states that support more local control but still recognize the value of protecting roadless areas, Colorado and Idaho offer proven models. Their state-specific Roadless Rules exemplify a modern approach to upholding Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation legacy. They balance conservation with flexibility—preserving critical natural values while accommodating local needs and addressing the modern challenges of forest management. And with the federal process just beginning, there’s likely still time for other states to chart their own course—before the national rule is rolled back.

[i] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., Secretary Rollins Rescinds Roadless Rule, Eliminating Impediment to Responsible Forest Management (June 23, 2025), https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2025/06/23/secretary-rollins-rescinds-roadless-rule-eliminating-impediment-responsible-forest-management.

[ii] Id.

[iii] Exec. Order No. 14,225, 90 Fed. Reg. 11,365 (Mar. 6, 2025).

[iv] Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. §§ 551–559 (2023).

[v] Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation, 66 Fed. Reg. 3244 (Jan. 12, 2001) (codified at 36 C.F.R. pt. 294).

[vi] Reed Shaw, Setting the Record Straight on the APA’s Good Cause Exception, YALE J. ON REGUL.: Notice & Comment (Mar. 14, 2024), https://www.yalejreg.com/nc/setting-the-record-straight-on-the-apas-good-cause-exception-by-reed-shaw/.

[vii] Idaho Roadless Area Management, 36 C.F.R. §§ 294.20–294.29 (2024); Colorado Roadless Area Management, 36 C.F.R. §§ 294.40–294.49 (2024).

[viii] Matt Sedlar, Public Lands for Private Profit: USDA to Revoke Roadless Rule, CTR. FOR ECON. & POL’Y RES. (July 1, 2025), https://cepr.net/publications/public-lands-for-private-profit/.

[ix] 16 U.S.C. § 1131(a).

[x] Wilderness, U.S. FOREST SERV. (Sept. 29, 2015), https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/wilderness.

[xi] Robert Chaney, Trump to Rescind Roadless Rule, Ending Protections for 58 Million Acres Nationwide, MONT. FREE PRESS (June 24, 2025), https://montanafreepress.org/2025/06/24/trump-to-rescind-roadless-rule-ending-protections-for-58-million-acres-nationwide/.

[xii] U.S. DEP’T OF AGRIC., FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT: ROADLESS AREA REVIEW AND EVALUATION (RARE II), 1–9 (1979), https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5116928.pdf.

[xiii] Id.

[xiv] Memorandum from President Clinton to the Secretary of Agriculture (Oct. 13, 1999) (https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5137325.pdf).

[xv] Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation, 66 Fed. Reg. 3244.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Id.

[xviii] Roadless Areas Inventoried by State, U.S. FOREST SERV., https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/planning/roadless/state-maps (last visited July 14, 2025).

[xix] Chaney, supra note 11.

[xx] Wyoming v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 661 F.3d 1209 (10th Cir. 2011).

[xxi] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., What They Are Saying: Strong Support for Secretary Rollins’ Rescission of Roadless Rule, Eliminating Impediment to Responsible Forest Management (June 24, 2025), https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/news/press-releases/2025/06/24/what-they-are-saying-strong-support-secretary-rollins-rescission-roadless-rule-eliminating.

[xxii] Andy Geissler & Nick Smith, USDA Moves to Rescind the Roadless Rule, JULY 2025 NEWSL. (Am. Forest Res. Council), July 1, 2025, at 3, https://amforest.org/july-2025-newsletter/.

[xxiii] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xxiv] Geissler & Smith, supra note 22, at 3.

[xxv] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xxvi] Ignacio Elorrieta & Concepción Rey, Mechanisms for the Internalization of the Environmental Benefits of Forests and The Application to Forest Fire Prevention, 2008 PROCS. OF THE SECOND INT’L SYMP. ON FIRE ECONS., PLAN., & POL’Y: A GLOB. VIEW 35, https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/34437.

[xxvii] Chaney, supra note 11.

[xxviii] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation, 66 Fed. Reg. 3.

[xxxiii] See Brooke Rollins, Opinion: This is how we manage forests better, DESERET NEWS (June 24, 2025, 6:00 PM), https://www.deseret.com/opinion/2025/06/24/roadless-rule-in-forests-is-going-away/.

[xxxiv] Wyoming v. U.S. Dep’t of Agric., 661 F.3d 1209 (10th Cir. 2011).

[xxxv] Id.

[xxxvi] Rollins, supra note 33.

[xxxvii] Id.

[xxxviii] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xxxix] Rollins, supra note 33.

[xl] Id.

[xli] Press Release, U.S. Dept’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xlii] Id.

[xliii] Mike Koshmrl, Trump’s Ag Boss Is Cutting 3.3M ‘Roadless’ Acres from 9 National Forests in Wyoming, WYOFILE (June 24, 2025), https://wyofile.com/trumps-ag-boss-is-cutting-3-3m-roadless-acres-from-9-national-forests-in-wyoming/.

[xliv] Id.

[xlv] Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Agric., supra note 21.

[xlvi] Id.

[xlvii] Memorandum from President Clinton to the Secretary of Agriculture, supra note 14.

[xlviii] Id.

[xlix] Id.

[l] Press Release, Ctr. for W. Priorities, Statement on Trump administration attempt to rescind Roadless Rule (June 23, 2025), https://westernpriorities.org/2025/06/statement-on-trump-administration-attempt-to-rescind-roadless-rule/.

[li] Carter Stone, Andrew Hudak, & Penelope Morgan, Forest Harvest Can Increase Subsequent Forest Fire Severity, 2008 PROCS. OF THE SECOND INT’L SYMP. ON FIRE ECONS., PLAN., & POL’Y: A GLOB. VIEW 525, https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/34437.

[lii] John Loomis et al., The Influence of Ethnicity and Language on Economic Benefits of Forest Fire Prevention From Prescribed Burning and Mechanical Fuel Reduction Methods, 2008 PROCS. OF THE SECOND INT’L SYMP. ON FIRE ECONS., PLAN., & POL’Y: A GLOB. VIEW 111, https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/34437.

[liii] Morgan Lee & Becky Bohrer, Trump Administration Plans to Rescind Rule Blocking Logging on National Forest Lands, AP NEWS (June 23, 2025), https://apnews.com/article/logging-national-forests-0607a77e0ab812ea6fa609034fbb20d9.

[liv] Koshmrl, supra note 43.

[lv] Why It’s Important to Keep the Wildest Forests Free of Roads and Logging, WILDERNESS SOC’Y (Nov. 12, 2019), https://www.wilderness.org/articles/blog/why-its-important-keep-wildest-forests-free-roads-and-logging.

[lvi] Press Release, Ctr. for W. Priorities, supra note 50.

[lvii] Chaney, supra note 11.

[lviii] Id.

[lix] Id.

[lx] Matt Sedlar, Public Lands for Private Profit: USDA to Revoke Roadless Rule, CTR. FOR ECON. & POL’Y RES. (July 1, 2025), https://cepr.net/publications/public-lands-for-private-profit/.

[lxi] Id.

[lxii] Roadless, THE SMOKEY WIRE: NAT’L FOREST NEWS & VIEWS (June 24, 2025), https://forestpolicypub.com/category/roadless/.

[lxiii] Chaney, supra note 11.

[lxiv] Id.

[lxv] Patrick Lohmann & Steurer Mary, As USDA Announces Plans to Repeal ‘Roadless’ Rule, ND Has 250,000 Acres That Could Be Affected, N.D. MONITOR (June 27, 2025, 1:48 PM), https://northdakotamonitor.com/2025/06/27/usda-secretary-in-santa-fe-announces-agency-intends-to-repeal-clinton-era-roadless-rule/.

[lxvi] Koshmrl, supra note 43.

[lxvii] Ken Rait, Americans Support ‘Roadless Rule’ to Protect Remarkable Forests, PEW (Mar. 13, 2019), https://www.pew.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2019/03/13/americans-support-roadless-rule-to-protect-remarkable-forests.

[lxviii] Special Areas; Roadless Area Conservation, 66 Fed. Reg. 3244.

[lxix] Id.

[lxx] Roadless Areas, U.S. FOREST SERV., https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/planning/roadless (last visited July 9, 2025); Learn, REGULATIONS.GOV, https://www.regulations.gov/learn (last visited July 9, 2025).

[lxxi] Id.

[lxxii] Learn, supra note 70.

[lxxiii] Id.

[lxxiv] Id.

[lxxv] Geissler & Smith, supra note 24, at 4.

[lxxvi] Id.

[lxxvii] Nicole Blanchard, USDA to End Rule That Kept Logging from National Forests. What’s It Mean for Idaho?, IDAHO STATESMAN (June 25, 2025), https://www.idahostatesman.com/outdoors/article309401225.html.

[lxxviii] Id.

[lxxix] Id.

[lxxx] Id.

[lxxxi] Michael Booth, Colorado’s Millions of Acres of Roadless Areas Are Safe from Trump Rule Reversal — for Now, COLO. SUN (June 26, 2025), https://coloradosun.com/2025/06/26/colorado-roadless-rule-safe-intact-trump/.

[lxxxii] Id.

[lxxxiii] Id.