Grasshoppers of Wyoming and the West

Entomology

Redshanked Grasshopper

Xanthippus corallipes (Haldeman)

|

Distribution and Habitat

X. corallipes continental distribution map >

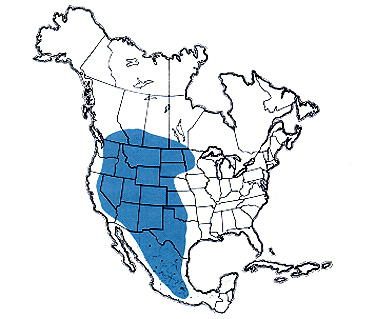

X. corallipes continental distribution map > The redshanked grasshopper ranges widely in western North America, inhabiting the grasslands and shrub-grass communities. The species is also present in clearings of montane forests and in open vegetated areas above timberline.

Economic Importance

This grasshopper feeds on quality forage grasses and is a potentially damaging species. Because the adults are usually present in low densities (from less than 0.1 up to 0.2 grasshoppers per square yard) in spring at a time when grasses have adequate moisture, most populations do no measurable damage to forage. Occasionally populations erupt as in 1989 in western Utah, where densities of 18 to 20 adults per square yard damaged not only rangeland grasses but also cultivated crested wheatgrass. In several rangeland areas they literally ate everything green, both grasses and forbs, down to the ground. A year later in Utah the outbreak persisted, and in certain areas adults flew from drought-stricken grassland to alfalfa fields where they fed on the crop.

The redshanked grasshopper is a large species. Live weights of males from mixedgrass prairie average 607 mg and of females 1,352 mg (dry weight: males 117 mg, females 442 mg).

Food Habits

The redshanked grasshopper feeds almost exclusively on grasses and sedges. In spring both the nymphs and the adults feed heavily on the green, early growth of cool-season plants: western wheatgrass, needleandthread, junegrass, needleleaf sedge, downy brome, and sixweeks fescue. In May when the foliage of blue grama, a warm-season grass, has grown plentiful, this species becomes an important item in the diet. After seeding early in the season, downy brome and sixweeks fescue die, turn brown, and become unpalatable. In late summer and early fall the new generation of nymphs feed heavily on blue grama.

A total of 22 species of grasses, two species of sedges, and one rush have been found in crop contents of the redshanked grasshopper. Because of its wide distribution in diverse habitats, known host plants are undoubtedly far short of the actual numbers eaten. Trace quantities of forbs (29 species), fungi, and arthropod parts have been found in crop contents. An apparent exception is the large quantity (17 percent dry weight) of the forb, woolly plantain, found in the crops of ten adults in July on the shortgrass prairie of northeastern Colorado.

Observation of the feeding of one adult female in the mixedgrass prairie of eastern Wyoming suggests that this grasshopper feeds on the ground in a horizontal position. The female fed on four western wheatgrass plants from 10:53 to 11:03 a.m. DST. Crawling and foraging on the ground, she raised her head upon contacting a host plant and cut a leaf an inch above ground level, then fed on the felled leaf from the cut end to the tip. She handled the leaf with her front tarsi from a horizontal position on the ground. Laboratory observations were made of late instar nymphs feeding from a horizontal ground position on dry fallen leaves of downy brome while housed in a gallon cage with soil as the floor. These observations indicate that the redshanked grasshopper may feed on ground litter as well as on green leaves that they cut.

Dispersal and Migration

The redshanked grasshopper has strong powers of flight. Wings of both males and females extend beyond the end of the abdomen. Evasive flights range from 4 to more than 30 feet. The flights are straight or sinuous at heights of 1 to 3 feet. They are accompanied by loud crepitation. The fleeing grasshopper lands horizontally on the ground and faces away from the intruder.

Little information is available on its dispersal and possible migration. Populations in habitats at different altitudes west of Boulder, Colorado did not disperse into nonresident habitats. In the recent outbreak in Utah, however, adults were observed to fly from denuded grass habitats to nearby alfalfa fields.

Identification

The redshanked grasshopper, a large rangeland species (Fig. 7 and 8), is present as an adult in spring. The adults are conspicuous in the habitat, as they crepitate loudly during evasive flight and reveal their yellow, dark-banded wings. A diagnostic character is the clearly defined dark brown maculations of the tegmina (Fig. 9).

The pronotum is heavily nodulate and rugose; the median carina is low and cut twice in front of the middle. The hind femur has three diagonal dark brown bands on its outer face and a solid bright red or deep blue inner face. The hind tibia is either entirely red or is yellow on the outer face and red on the inner face.

The nymphs are identifiable by their shape, structures, and color patterns (Fig. 1-6).

1. Head rounded with face nearly vertical; lateral foveolae triangular; vertex with integument wrinkled except smooth in instar I. Maxillary and labial palps with segments pale gray and proximal ends ringed black, terminal segment with an additional black ring near tip; rings fading in instars IV to VI.

2. Pronotum with integument smooth in instar I, nodulate and wrinkled instars II to VI; median carina of disk low but equally elevated throughout, entire in instar I, cut twice in instars II to VI, principal sulcus deeply cut, front sulcus often faintly cut; lateral carinae of disk pale yellow; a light V-shaped figure on anterior half of disk; light lateral lines on posterior half extend to arms of V (see Figure 2 for side view).

3. Hind femur with lower carina expanded into a conspicuous keel (instars III to VI); outer face tan with three diagonal brown bands, inner face dark blue with pale yellow band next to knee, sometimes a smaller second band near middle, orange or red interfusions on inner face in instars V and VI. Hind tibia shiny dark blue to black in instars I and II, orange or dark blue with orange patches in instars III to VI.

4. Body color brown or gray with many dark brown spots; individuals developing on red soils become red and lose color patterns and majority of markings in instars III to VI (see Figure 4).

Hatching

Studies of egg development indicate that northern populations of the redshanked grasshopper have a two-year life cycle while southern populations have a one-year life cycle. In central Saskatchewan eggs laid in spring develop to an advanced stage by fall, at which time they go into diapause. The diapause is broken during winter and the eggs hatch the following summer. Eggs laid in the laboratory by females originating from a population in Pima County, Arizona hatched at room temperature in five weeks. This result indicates a one-year life cycle for southern populations.

In southern populations eggs of the redshanked grasshopper hatch in mid-summer, two to four weeks after the hatching of the brownspotted grasshopper, Psoloessa delicatula, and the specklewinged grasshopper, Arphia conspersa. In the mixedgrass prairie of western North Dakota at altitudes of 2,000 feet, hatching of the redshanked grasshopper begins in mid-July; in the shortgrass prairie of northeastern Colorado at altitudes of approximately 5,400 feet, hatching begins the last week of July; while in the mixedgrass prairie of eastern Wyoming at altitudes of 4,400 feet to 5,300 feet, hatching begins in mid-August. The period of hatching lasts approximately four weeks.

Nymphal Development

The redshanked grasshopper develops steadily during the warm weather of summer and early fall. In the mixed-grass prairie of western North Dakota the nymphs become third instars by the first of August, while in the prairies of eastern Wyoming and Colorado, they become third instars by the end of August. Males of this species have five or six instars and females have six. By the end of October nymphs have reached the overwintering instars, mainly fifth and sixth. They may take shelter on the ground surface under litter and in small soil depressions. During unseasonably warm weather in winter, some nymphs become active and are able to evade an intruder by jumping. For example, three late instars were caught on 7 February 1991 after they jumped in a habitat of mixedgrass prairie on the outskirts of Laramie, Wyoming. As the sun waned during the 15-minute search (2:45 to 3:00 p.m.), the soil surface temperature decreased from 66 to 62°F and air temperature 1-inch high in shade decreased from 51 to 50°F. The nymphs emerge from their overwintering quarters in March and develop to the adult stage in April and May.

Adults and Reproduction

The adults, prevalent in May and June, remain in the same habitat in which they develop as nymphs. Late metamorphosing adults may survive well into August. Little is known about the maturation of adults. Courtship apparently occurs without flight displays and is mediated by stridulation of the males. The male rubs a ridge on the inside of the hind femur against a linear series of nodes on a raised vein of the tegmen. To the human ear, the sound produced is a chirp and is the primary courtship signal of the male. A visual signal may also be involved when a stridulating male raises his hindlegs and exposes the bright red or dark blue inner surfaces of the tibiae and femora.

Although the act of oviposition in the natural habitat has gone undescribed, circumstantial evidence indicates the female selects bare ground for this purpose. In a laboratory terrarium transplanted with vegetation from the mixedgrass prairie, females chose to oviposit in bare soil. Over one hour was required to complete an oviposition. After extracting her abdomen, a female takes a minute to brush soil over the hole with her hind tarsi. Females deposit eggs deeply in the soil; eggs lie at a depth of 2 to 3 inches.

The egg pod is two and three-quarters inches long and slightly curved (Fig. 10). The diameter of three-eighths inch in the bottom region containing the eggs is greater than in the top region of froth. Eggs are brown and 6 to 6.5 mm long and number about 32 per pod.

Population Ecology

Little information is available on the population ecology of the redshanked grasshopper, however, it is known that populations normally fluctuate at low densities, increasing from less than 0.1 adult per square yard in some years up to 0.2 adult per square yard in others. Populations have also been observed to increase explosively as in the recent outbreak in Utah, where adults have reached densities up to 20 per square yard.

Daily Activity

Observation of daily activity of the redshanked grasshopper has been limited because of low population densities in study sites. In spring and in fall the nymphs endure freezing temperatures during the night. They may find shelter in the litter or in small soil depressions or may sit exposed on the soil surface. They assume a posture that appears to keep them as warm as the environment allows by minimizing the area of exposure to the cold air. They sit horizontally on the ground surface with body appressed to the soil, legs flexed and held close to the body, and the antennae turned back and against the sides of the head.

Like the nymphs, adults appear to rest horizontally on the soil surface at night. Adults have been flushed from the ground surface and may jump to evade capture in the morning (8:30 a.m. DST) when ground surface temperature is 60°F. Later (9:30 a.m.), at soil surface temperature of 76°F, flushed adults fly evasively from the ground. One observation was made of a female basking late in the morning (10:45 a.m., soil temperature 80°F) with her left side perpendicular to the sun's rays. This same female began to feed at 10:55 a.m.

When temperatures rise above tolerable levels, greater than approximately 130°F at the soil surface, females have been observed to move across the ground to the shady side of shrubs and males have been observed to climb plants, such as western wheatgrass, to 3 to 6 inches above the soil surface and then rest on the shady side of the plant.

Selected References

Alexander, G. and J. R. Hilliard, Jr. 1969. Altitudinal and seasonal distribution of Orthoptera in the Rocky Mountains of northern Colorado. Ecol. Monogr. 39: 385-431.

Frase, B. A. and R. B. Willey. 1981. Slowed motion analysis of stridulation in the grasshopper, Xanthippus corallipes (Acrididae: Oedipodinae). Can. J. Zool. 59: 1005-1013.

Onsager, J. A. and G. B. Mulkern. 1963. Identification of eggs and egg-pods of North Dakota grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae). North Dakota Agr. Exp. Stn. Bull. 446 (Technical).

Otte, D. 1984. The North American Grasshoppers, Vol. II Acrididae, Oedipodinae. (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Pfadt, R. E. and R. J. Lavigne. 1982. Food habits of grasshoppers inhabiting the Pawnee Site. Wyoming Agr. Exp. Stn. Sci. Monogr. 42.

Pickford. R. 1953. A two-year life-cycle in grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae) overwintering as eggs and nymphs. Can. Entomol. 85: 9-14.

Ueckert, D. N. and R. M. Hansen. 1971. Dietary overlap of grasshoppers on sandhill rangeland in northeastern Colorado. Oecologia 8: 276-295.