Research Project 1

How do worms shed their skin that's also their skeleton?

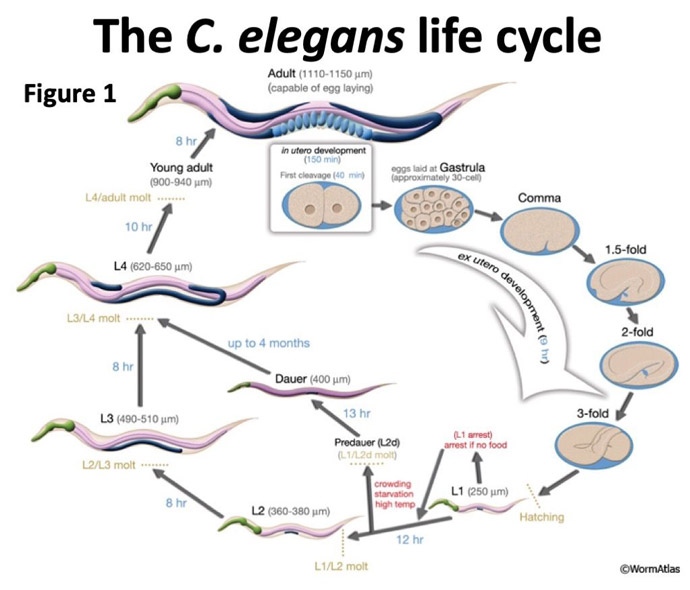

Molting or shedding is common to many life forms including insects and roundworms. Nevertheless, the specific purpose and process of molting tends to vary considerably between species. Round worms typically undergo four cycles of molting during their larval stage of development (Figure 1). In the case of C. elegans, molting likely accommodates the rapid growth that accompanies this period of development. Each new skin, or cuticle, has extramaterial and elasticity built into it, similar to the idea of buying clothing for kids that allows for ‘room to grow’.

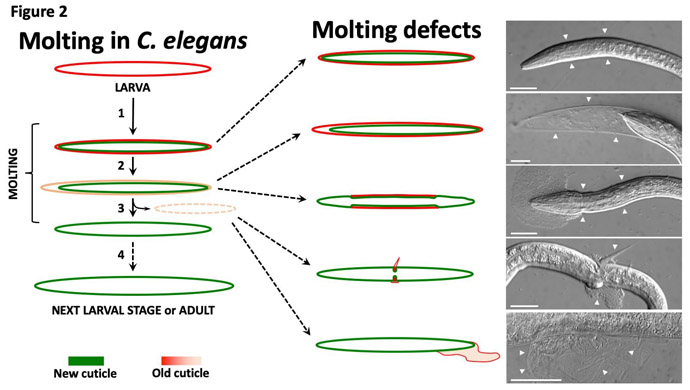

At heart, molting can be thought of as having two main steps (Figure 2). The first is to synthesize a new cuticle underneath the old cuticle. The second involves releasing the old cuticle by partially degrading it and also by the worm carrying out a series of acrobatic movements to help it break free from the old cuticle. In reality, it’s quite a bit more complicated than that. One factor to consider is that the old cuticle may need to be partially loosened in order to create room for new cuticle synthesis. In addition, cable-like attachments between underlying muscles and the old cuticle must be released and rapidly re-connected to the new cuticle. Without the relatively stiff cuticle to pull against, worms can’t move, just like humans couldn’t move without an endoskeleton. Although the overt mechanical and behavior aspects of C. elegans molting were first described more than 40 years ago, the underlying molecular, genetic, and physiological mechanisms controlling molting in nematodes are not well understood.

There are several reasons why studying nematode molting is of interest to scientists. One has to do with nematodes themselves. Although the C. elegans we study are free-living soil nematodes, many other nematodes are parasitic, using humans as a host. In fact, it is estimated that nearly 3 billion people are infected with nematodes worldwide–more than one-third of the world’s population! Furthermore, parasitic nematodes take an enormous toll on both plants and animals used for human agriculture, resulting in billions of dollars in economic losses, to speak nothing of devastating effects of malnutrition. Developing new drugs that specifically target the nematode molting cycle could be a kind of “silver bullet”, allowing for the selective eradication of nematodes inside the human body. In addition, the process of molting in nematodes shares a number of common features with both normal and disease-related processes in humans. By studying molting in worms, we can gain insights into fundamental mechanisms of biology shared by both worms and humans.

To understand nematode molting at a molecular and cellular level, we’ve taken a classical genetics approach. Namely, we’ve carried out genetic screens for mutant worms that are defective at molting. Typically, this leads to worms that fail to cast off their old cuticles (Figure 2). By discovering the genes that are defective in these molting mutants,we can figure out which genes and molecular processes are required for normal molting. This is a non-biased and open-ended type of approach. We essentially figure how biological processes work by randomly breaking them, finding out what got broke, and then putting the pieces of the puzzle together through experimentation and hypothesis testing. An example of this is our discovery of new genes involved in the transportation of proteins and membranes to and from the outer surface of skin cells.