Grasshoppers of Wyoming and the West

Entomology

Largeheaded Grasshopper

Phoetaliotes nebrascensis (Thomas)

|

Distribution and Habitat

P. nebrascensis continental distribution map >

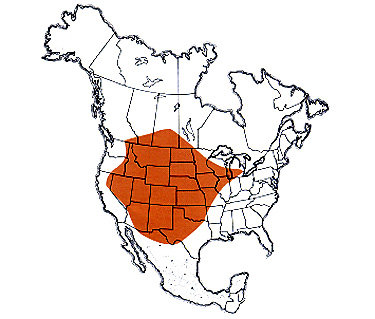

P. nebrascensis continental distribution map > The largeheaded grasshopper ranges widely in the grasslands of North America. Preferring a habitat of tall, lush grasses, it is often the dominant grasshopper species in the tallgrass prairie and is a common inhabitant in taller types of the mixedgrass prairie. In shorter types it may be locally abundant in patches of tall grass growing in swales, ravines, along streams, and in roadsides.

Economic Importance

Feeding mainly on grasses, the largeheaded grass-hopper adds to the damage caused by infestations of rangeland grasshoppers. In the lush, tallgrass prairie, damage is visible but of little economic importance. Measurements of damage have not been successful in showing any statistical significance between treated and control plots. In the mixedgrass prairie, this grasshopper congregates in swales, especially during droughts, and consumes much of the forage that is in short supply for livestock and wildlife. In fall, adults may invade fields of winter wheat and feed on the seedlings, consuming the entire plant to ground level.

The female weighs twice as much as the male. Live weights of males collected from the mixedgrass prairie of southeastern Wyoming averaged 206 mg and females averaged 419 mg (dry weights: males 63 mg, females 137 mg).

Food Habits

The largeheaded grasshopper feeds almost exclusively on grasses, an unusual habit for a spurthroated grasshopper. It feeds heavily on little bluestem, big bluestem, and Kentucky bluegrass in the tallgrass prairie, while in the mixedgrass prairie it feeds principally on western wheatgrass. Populations in the bunchgrass prairie of west-central Idaho feed on bluebunch wheatgrass, but in its absence they feed on sand dropseed.

Extensive laboratory feeding tests reveal that largeheaded grasshoppers surprisingly prefer several species of grasses and forbs to their usual host plants. The preferred plants in the laboratory include the grasses: downy brome, Scribner panicum, barnyardgrass, witchgrass, junegrass, and foxtail barley; and the forbs: dandelion, meadow salsify, and skeletonweed. Plants as acceptable as the natural host plants include green bristlegrass and smooth brome, both introduced species. Smooth brome grows profusely in roadsides and often harbors dense populations of the largeheaded grasshopper. Less attractive grasses include blue grama, buffalograss, sand dropseed, needleandthread, prairie sandreed, and Kentucky bluegrass. The latter grass, however, is ingested in considerable amounts when it occurs in the habitat.

In tall, lush grasses, the largeheaded grasshopper rests vertically head-up on the host plant. During feeding, it may remain in this position or it may turn around and face vertically head-down. In either orientation it eats the edge of the leaf, creating a long gouge along one side and leaving a narrow edge of the leaf intact. The feeding of a nymph (instar IV) on western wheatgrass resulted in a 30 mm long, 2 mm wide gouge in the middle of the leaf, with 1 mm wide edge left standing. As soon as a head-down individual finishes a feeding bout, it turns around and again rests vertically head-up.

Dispersal and Migration

Because the majority of adults of the largeheaded grasshopper develop short wings unsuited for flying, this form of the species cannot disperse or migrate very far. When the need arises, however, adults readily disperse within the locale of their habitats. On Montana rangeland in midsummer, they have been observed to move from drying vegetation to nearby green vegetation. When these green areas became dry, they moved to adjacent gullies where the grasses still remained green. In southeastern Wyoming short-winged adults moved from a draw that had dried out in October to nearby seedling winter wheat, a distance of 30 to 90 feet. A mark-and-recapture study of movement of short-winged adults in the Nebraska sand prairie indicated a net displacement of individuals 3 to 13 feet from one day to the next. The distance for an individual (a male) with the longest period between marking and recapture (14 days) amounted to 135 feet.

The less common long-winged adults have strong powers of flight and no doubt are able to disperse considerable distances. Perhaps during past times, development of large numbers of long-winged adults with subsequent dispersal resulted in the widespread geographic range of this species.

Identification

The largeheaded grasshopper, slim and medium-sized, possesses a very large head relative to the rest of the body. The face is slanted. Most adults have short wings that extend only to the second or third abdominal segment and end in a point (Fig. 6 and 7). The rarer long-winged individuals (0.5 to 5.5 percent in a population) have wings extending a few millimeters beyond the end of the abdomen. Infrequently, as much as 25 percent of a population is long-winged. The body color of live adults is primarily light gray, the venter is often yellow. Dried specimens usually turn tan. The dorsal stripe of the hind femur is brown or fuscous and invades the lower medial area. The hind tibia is blue. The male cercus is triangular, ending in a blunt point (Fig. 9).

The nymphs are distinguishable by their structure, color, and shape (Fig. 1-5).

1. The head is large relative to the rest of the body, face is slanted; antennae are filiform; fuscous vertical stripe below and horizontal stripe behind compound eye, both stripes contrasting noticeably with light gray of head; compound eye brown with white to pale tan spots.

2. Edge of pronotal disk with fuscous wedge-shaped stripe, wide anteriorly, narrowing posteriorly, faint in instar I.

3. Hind femur with pronounced dorsal stripe that extends into ventral half of medial area; hind tibia pale yellow with front fuscous in instars I to III, blue in instars IV and V.

Hatching

Hatching about one month after Ageneotettix deorum, the largeheaded grasshopper belongs to the late-developing group of species. In the tallgrass prairie of eastern Kansas, eggs may begin to hatch as early as May 22. In the mixedgrass prairie of southeastern Montana hatching begins as early as June 8 and in southeastern Wyoming as early as June 13. Hatching continues for a period of four weeks or longer. Possible abiotic reasons for the late hatch include the relatively deep location of the eggs in the soil (an inch or more) and the cool soil temperatures of the lush habitat. In newly burned tallgrass prairie, eggs hatch two weeks earlier than in unburned tallgrass prairie due to the exposed soil warming more quickly in the spring than soil covered by deep litter of the unburned prairie.

Nymphal Development

The nymphs of the largeheaded grasshopper develop slowly. As measured by the time from first appearance of instar I to the first appearance of the adult, the nymphal period requires 55 days both in Kansas and Wyoming. The probable cause of this extended period is the habitual perching of nymphs on tall grasses. This location is usually several degrees cooler than the ground location of most rangeland species. Development of both males and females requires five instars for completion of the nymphal period.

Adults and Reproduction

Short-winged adults remain in the same general area in which the nymphs developed, but do move short distances to track greener and more nutritious host plants. The first adults appear in mid to late July in Kansas, while in southeastern Wyoming they appear during the first week of August.

Little is known about the maturation and reproduction of this grasshopper in nature. Laboratory cage tests suggest a high rate of fecundity. Short-winged females produced 120 eggs per capita during a reproductive period experimentally set at 25 days. Long-winged females produced fewer eggs because of the apparent necessity to divert part of the nutrient intake to the production of flight muscles and long wings.

No observations of courtship have been made, and published observations of mating are zilch. One mating pair was seen in the mixedgrass prairie of eastern Wyoming at 9:15 a.m. DST on 1 August 1968 and another in a roadside habitat dominated by smooth brome and western wheatgrass at 9:30 a.m. DST on 26 August 1993. In the latter case, the pair, which was basking vertically head-up 6 inches high on a smooth brome leaf, had assumed the usual mating position of grasshoppers (i.e., the male clinging on top of the female). The male's head rested immediately behind and above the female's. Because of the smaller size of the male, the female's genitalia had to curve up to meet the male's curving down.

The oviposition sites selected by females are uncertain. In a published study of grasshopper biology conducted in the sand prairie of southeastern North Dakota, females were said to oviposit in vegetated sites. However, it is not clear whether the females oviposited into or close to crowns or into small bare areas interspersed among the plants. The egg-laying behavior of females confined in a laboratory terrarium of sandy loam soil and mixedgrass prairie turf further confuses the issue. During ten days of confinement, five short-winged females deposited five pods in the bare soil and none in the turf.

The pods are 1 to 1 1/4 inches long and slightly curved in the region of the eggs (Fig. 10). The pods of short-winged females usually contain 28 eggs, equalling the total number of ovarioles, while the pods of long-winged females usually contain from 20 to 24 eggs. Eggs range in color from olive to brownish yellow and measure from 4.1 to 4.4 mm in length.

Population Ecology

Populations of the largeheaded grasshopper reach their highest densities in habitats of lush tall grasses. In the Flint Hills, a tallgrass prairie region of eastern Kansas extending into Oklahoma and Nebraska, the species is common and often dominant. This large natural grassland, over 200 miles long from the north to the south and as much as 50 miles wide, appears to be the species center of distribution. Densities regularly number three to four young adults per square yard and probably increase to much higher densities during outbreaks.

The distribution of the largeheaded grasshopper extends west into the mixedgrass prairie, where the species occupies the more luxuriant aspects, particularly swales, riparian areas, and roadsides. In these sites, stands of western wheatgrass grow tall and rank, providing favorable habitats and an abundance of food. Populations aggregate in these habitats reaching densities as high as 12 young adults per square yard and often achieve dominance in the grasshopper assemblage. In contrast, surrounding mixedgrass prairie usually harbors less than one young adult per square yard, and the species occupies a low rank in the assemblage.

This grasshopper inhabits other grasslands of the West, usually in limited areas and at low densities. In the shortgrass prairie the species is rarely a member of the grasshopper assemblage, but in northwestern Texas it was a common species on rangeland in two out of seven years (1966-72). The desert prairie does not often harbor the largeheaded grasshopper, but south of Tucson in an ungrazed sanctuary of the Audubon Society it inhabits level uplands covered by luxuriant stands of blue grama, plains lovegrass, and wolftail grass. Average seasonal densities from 1985 to 1989 ranged from 0.1 to 0.3 per square yard. In 1989, at 0.3 per square yard, the largeheaded grasshopper became the dominant species in a low-density assemblage of nine species. This grasshopper is rarely found in sites of the bunchgrass prairie, but in Idaho it is one of the major species living on steep hillsides vegetated with bluebunch wheatgrass. Densities, however, are low, usually less than one per square yard.

Daily Activity

In its preferred habitat of tall grasses the largeheaded grasshopper behaves as a phytophilous species, sitting on stems and leaves for most of the day and night. Warm nights are spent resting vertically, head-up on grass leaves and stems at heights of 6 to 12 inches. Cold nights are spent lower down on the grass or under litter.

In the morning on a clear day, two to three hours after sunrise, the nymphs and adults, resting vertically head-up on tall grasses, begin to bask by turning a side perpendicular to the rays of the sun and lowering the associated hindleg. This orientation raises their body temperature, which has fallen during the night, to that of the habitat, which in Wyoming ranges from 50 to 60½F. They remain quietly basking, occasionally stirring, for two to three hours and eventually become active in mid morning. Individuals in habitats of short and mid grasses usually spend the night under litter. In the morning they bask sitting horizontally on bare ground.

After basking, the grasshoppers infrequently move about on the tall grasses by crawling or jumping from one plant to another. They may also back down a grass stem or turn around and crawl head-down to reach the ground. On the ground they crawl and hop intermittently, moving a net distance of 15 feet in 30 minutes. Grasshoppers perched on tall grass have been observed to feed from early morning to evening (7 a.m. to 6 p.m. DST). More observations of feeding, however, have been made from 9 to 11 a.m. DST than during any other two-hour period.

A second period of basking occurs in late afternoon. At this time the grasshoppers bask for approximately two hours. Near sunset, when shadows engulf their habitat, they take nighttime positions. Those basking vertically head-up on tall grasses may remain there, or back down several inches, while others may find shelter under ground litter.

References

Anderson, N. L. and J. C. Wright. 1952. Grasshopper investigations on Montana rangelands. Montana Agr. Exp. Stn. Bull. 486.

Banfill, J. C. and M. A. Brusven. 1973. Food habits and ecology of grasshoppers in the Seven Devils Mountains and Salmon River Breaks of Idaho. Melanderia 12: 1-21.

Bock, C. E. and J. H. Bock. 1991. Response of grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acrididae) to wildfire in a southeastern Arizona grassland. Amer. Midl. Nat. 125: 162-167.

Evans, E. W. 1989. Interspecific interactions among phytophagous insects of tallgrass prairie: an experimental test. Ecology 70: 435-444.

Gaines, S. B. 1989. Experimental analyses of costs and benefits of wing length polymorphism in grasshoppers. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Mulkern, G. B. 1980. Population fluctuations and competitive relationships of grasshopper species (Orthoptera: Acrididae). Trans. Amer. Entomol. Soc. 106: 1-41.

Pruess, K. P. 1969. Food preference as a factor in distribution and abundance of Phoetaliotes nebrascensis. Annals Entomol. Soc. Amer. 62: 323-327.